When the rut is on or the powder flies, my family drops everything and heads for the hills. Our love for the mountains inspired us to name our daughter, Skade, after the Norse goddess of winter, skiing, and bowhunting; Skaði. Like all parents, we’re excited to share our passions with Skade. But over her lifetime the things we love about the mountains, from huckleberry picking to high country hikes, will be affected by climate change. That’s why, when we discovered a new species of jumping-slug living in the coldest nooks and crannies of northern Idaho, we named it Skade’s jumping-slug (Hemphillia skadei). The name skadei recognizes the cool air temperatures this mountain dwelling species is associated with, acknowledges the cultural value skiing and hunting provide to many people who share its range, and is symbolic that today's children will be living with the full effects of climate change toward the turn of the century. Our findings were published the April, 2018 issue of the Canadian Journal of Zoology.

"We hope the name of this species will inspire other Idaho families to learn how our changing climate is affecting their outdoor lifestyle and the survival of the wild animals around them," says lead author Michael Lucid.

Jumping-slugs are a genus (Hemphillia) of slugs that are found only in the Pacific Northwest. Six species are known to exist; three live in coastal areas and three are found in the Inland Northwest of Idaho, Montana, Washington, and British Columbia. They can be distinguished from other northwest slugs by a pronounced ‘hump’ on their back which contains a ‘vestigial’ shell. That is a small bit of fingernail-like hard shell that is a remnant of their evolutionary relationship with snails. And yes, they ‘jump’. Thought to be a defense against predatory snails and beetles jumping-slugs do a sort of squirming dance that gives them their jumping reputation.

Skade's Jumping-slug (Hemphillia skadei)

Skade’s jumping-slug is a ‘cryptic’ species. That means on the outside, to the human eye at least, it looks just like its closest relative the pale jumping-slug. We began to suspect we had found an un-described species (a species not known to science) when we were doing a massive snail and slug inventory as part of the Multi-species Baseline Initiative (MBI). Many of the Species of Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN) in Idaho’s State Wildlife Action Plan (SWAP) are gastropods (snails and slugs) which were thought to be very rare. The problem was, no one had done a really thorough search for them. So we included snails and slugs in our MBI survey to figure out which species were rare and which were common. To validate our species identifications, we sent some of our samples to a genetics lab. When we got the results back began to suspect we had a new species.

Skade's (left) and Pale (right) jumping-slug.

The lab sequenced a portion of one gene for us. The results we got back are a series of four letters which represent the different bases that make up our DNA; Adenine, Guanine, Cytosine, and Thymine. The samples that came back from animals we had identified as pale jumping-slugs actually looked quite different from each other, kind of like this:

Species 1: AAGCTTTCAGAGTAGA

Species 2: AAACTTCCAGAGTTGA

We looked again at our specimens but couldn’t find a visual difference in the species. So we decided to proceed in two ways: 1) we would sequence portions of two more genes and 2) send some preserved specimens to our friend (and co-author) Dr. Lyle Chichester, who is an expert in slug reproductive anatomy.

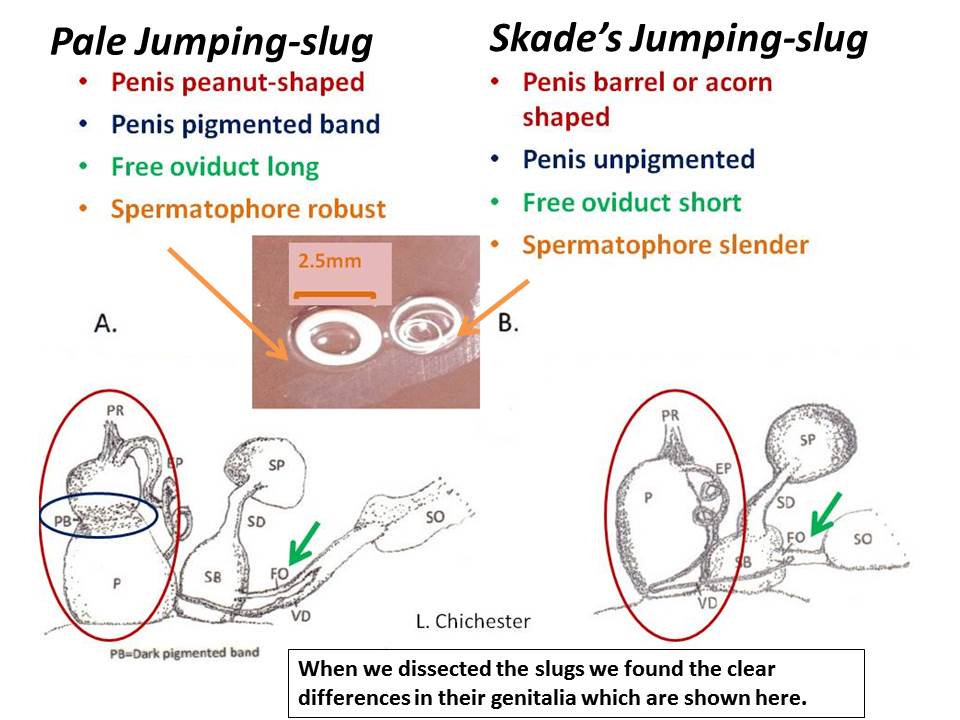

After some very careful dissections, Dr. Chichester determined there were four differences in the reproductive system of specimens.

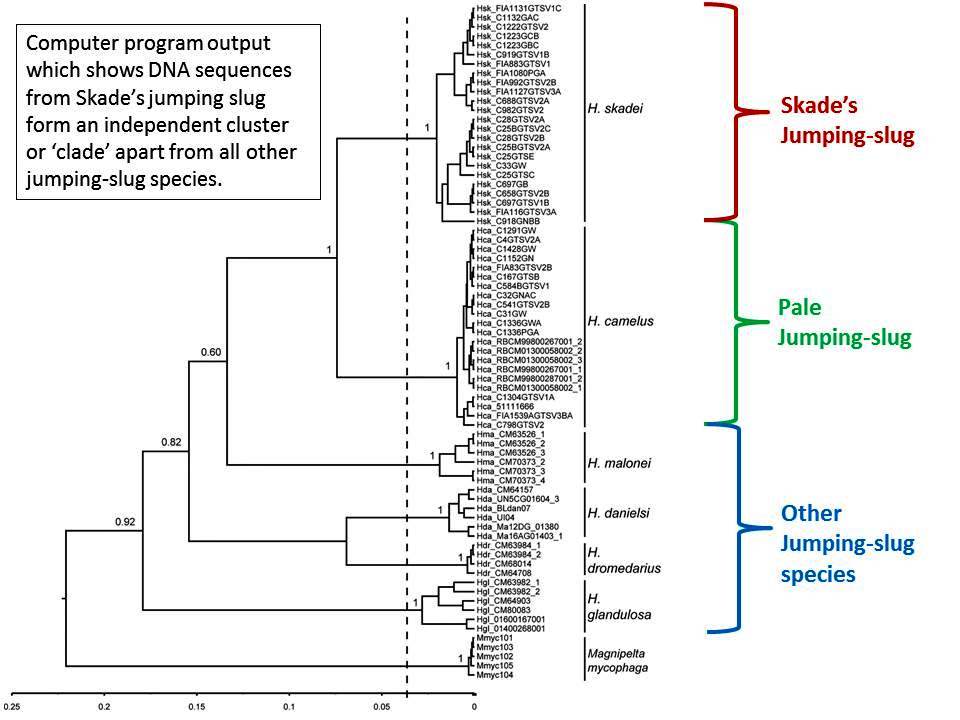

When we ran the DNA sequences thorough a computer program is also showed we had a species which was distinct from all of the other jumping-slugs.

Now that we were sure we had a new species on our hands it was time to describe what we knew about its natural history.

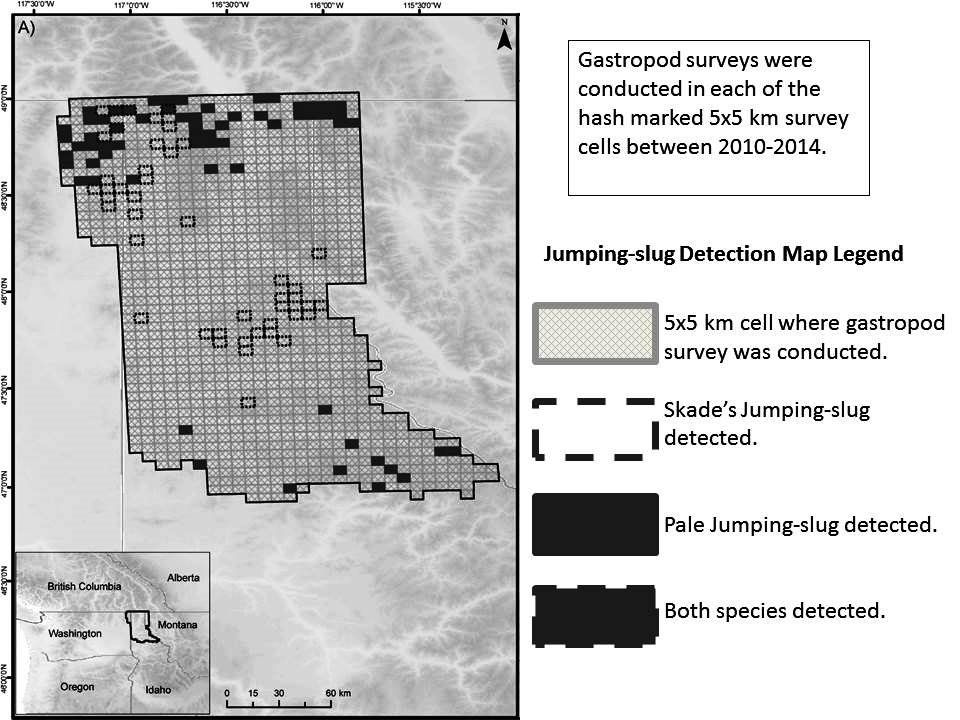

Skade's jumping-slug has a very interesting distribution as it is found in the middle of the range of pale jumping-slugs. Skade’s was the only jumping-slug species we found in the Coeur d’ Alene Mountains but we found pale jumping-slugs to the south in the Joe and to the north in the Selkirks and Purcells. Skade’s jumping-slug is found northward into the Selkirks all the way up to where, in a few spots, we found it at the same survey sites as pale jumping-slugs. This is what we call a species ‘contact zone’. These species probably became isolated from each other in the past, possibly during the last ice age. Now, even though they are found right next to each other in the Selkirks, it appears they have developed enough differences in their reproductive anatomy that they can’t breed with each other anymore.

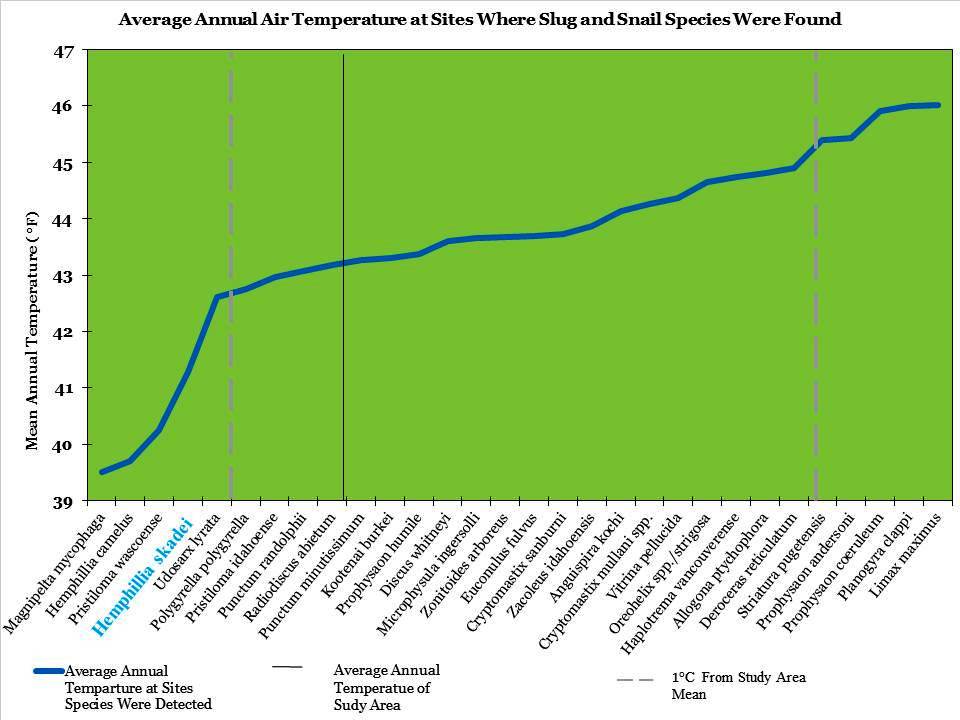

The other thing we know is Skade’s jumping-slug is found in locations that have much cooler air temperatures than the rest of northern Idaho. During MBI we deployed over 1,000 air temperature data loggers at sites where we did wildlife surveys. We recorded the temperature every 90 minutes for at least a year at each site. We found that 3 slugs and 1 snail were found at sites averaged at least 1°C cooler than the average study area air temperature. Skade’s jumping-slug is listed as a SGCN in Idaho’s SWAP because it is may be sensitive to climate change and its habitat may shrink or shift as the climate warms.

The future of the isolated cold spots Skade's jumping-slug calls home is uncertain. Climate change is bringing hotter, drier, smokier summers and wetter, warmer winters to north Idaho. This means more rain on snow events and possibly snowless winters in parts of our mountains. The severity of future climate change effects depends on emission levels and remains to be seen. But regardless of severity, it is clear is that we will all have to learn how to adapt to protect these places we cherish and the wildlife that call them home.