Winter is an extremely stressful time of year for mule deer in southeastern Idaho and is the single largest factor shaping deer numbers on the landscape from year-to-year. Freezing temperatures and snowfall dramatically reduce the amount and quality of available forage, deer function at a caloric deficit for several months, and large-scale die-offs (from starvation and exposure) can occur. Fawns approximately 6 months old at the beginning of winter are the first to die, followed by older and sickly individuals, and lastly, healthy adults during the most severe winters. Even during “normal” winters about 40% of the fawns that were alive in December will die before their first birthday. The most severe die-offs aren’t pretty, leaving carcasses littered across the terminal winter range, and the after-effects are felt and seen by sportsmen during the subsequent hunting seasons when deer are less abundant and hunter harvest can decrease dramatically.

The 2022-2023 winter in southeastern Idaho, western Wyoming, northern Utah, and northwestern Colorado was one of the most severe on record. Deep snows arrived in early November and persisted well into typical spring months. These conditions proved challenging for wildlife, especially mule deer. The 2016-2017 and 2018-2019 winters were similarly difficult, resulting in three challenging winters over a 6-year period and a severely depressed mule deer herd in some areas of southeastern Idaho. In response to these severe winters Idaho Fish and Game staff implemented emergency winter feeding operations in the hardest hit areas, closed wildlife management areas to human entry, adjusted antlerless harvest, worked with federal agencies on winter travel restrictions, and implemented an antler gathering season to reduce disturbance to deer.

This mule deer population decline is not unique to Idaho. Each of the states listed above experienced dramatic declines in mule deer abundance in some areas, and all of these states manage herds slightly differently. Some fed deer, some did not. Some cut buck tags, and some did not. However, all states, including Idaho, have experienced the same decline in deer abundance regardless of the varying efforts to reduce mortality.

Estimates of mortality from collared mule deer indicated 90% of fawns and 50% of adult female mule deer died in southeastern Idaho, similar to mortality in adjacent states. In January of this year, Fish and Game conducted an aerial survey of the Caribou mule deer herd (GMUs 66, 66A, 69, 71, 72, and 76) to obtain an accurate population estimate where the prior winter was the most severe. Fish and Game staff spent ~150 hours in helicopters completing this extensive and rigorous survey. The current Caribou mule deer population is estimated at ~13,000 total deer, down from nearly 23,000 estimated during the 2019 survey. In 2016, prior to the last significant winter, this mule deer population likely was in excess of 33,000 deer (the result of several mild winters) and has declined nearly 60% to current levels.

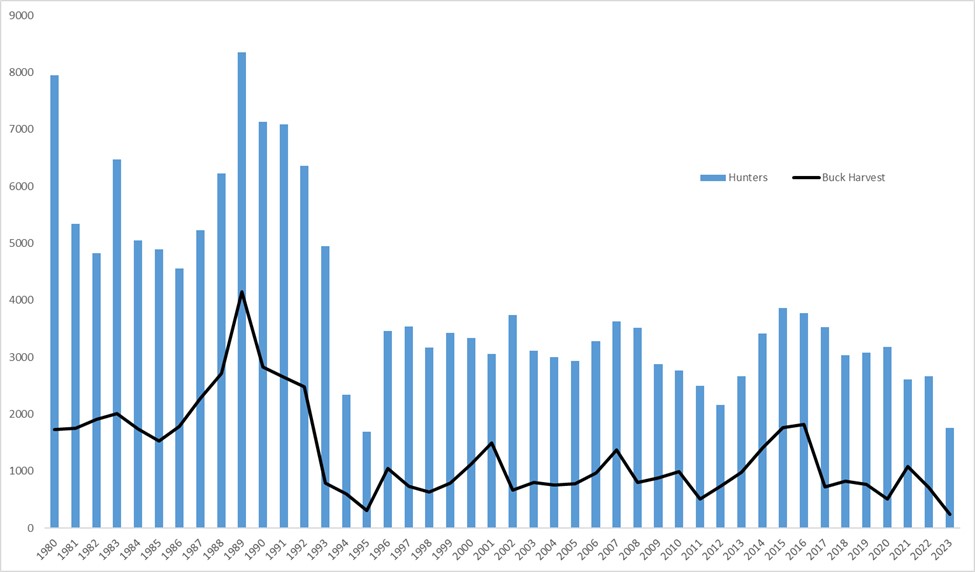

As expected, following a substantial decline in deer abundance, Fish and Game estimated one of the lowest hunter participation rates and deer harvest rates on record during the 2023 fall season. Although the current winter (2023-2024) has been favorable to mule deer, Fish and Game expects the 2024 fall to again be challenging for hunters in southeastern Idaho.