Money for wildlife conservation is a dwindling resource in a time when there has never been a greater need for it. The sweat equity of eight organizations, 200 citizen scientists, and a biologist’s survey tool showed what can be accomplished when the two are connected. This collaborative effort is now published for others to see and use in similar research.

Multispecies survey

There is a long tradition in wildlife management where researchers attempt to understand one species at a time. We call this 'single species management'. But in our quickly changing world there’s an urgent need understand more about the diversity of the wildlife we manage and we don’t have the time or money to do that one species at a time.

To that end, the Multispecies Baseline Initiative (MBI) developed a technique to survey multiple species at the same time including fisher, marten, wolverine, bobcats, coyotes, and more. We published our findings in the September issue of the Journal Ecology and Evolution: Winter bait stations as a multispecies survey tool. This open access journal article is available free of charge for anyone to read and we summarize the results below.

"This type of community effort combined with innovative wildlife survey techniques will help move wildlife management from the single species world to a multi-species, efficient, ecosystem based disciple" says lead author Lacy Robinson.

Videos at the end of this article capture the community effort behind the multispecies survey in North Idaho’s backcountry.

Step 1 - Winter Bait Stations

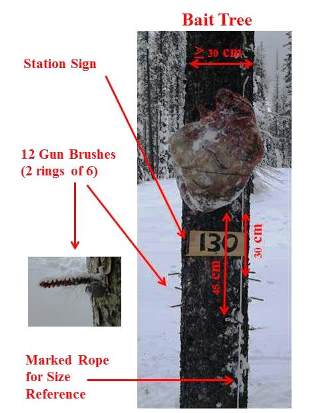

Winter bait stations are a pretty simple concept. We wire a piece of meat (usually a beaver) to a tree and put a remote camera on another tree. Under the beaver we put a couple rings of hair snares. So the bait attracts animals to the tree, the camera takes photos of the animals, and the snares collect DNA (hair) from animals as they climb the tree.

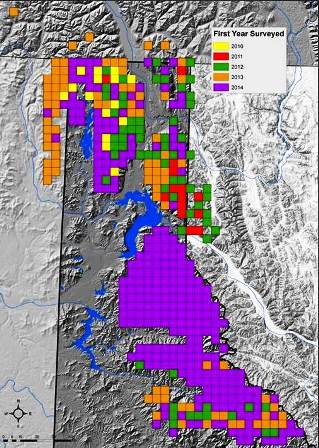

Although setting up the stations was fairly straight forward, deploying all 497 of them across every nook and cranny of our Idaho Panhandle and adjoining mountain range study area was serious work! Eight organizations and over 200 volunteer citizen scientists worked together over four winters to run bait stations across north Idaho's rugged terrain. When it was all said and done we had collected nearly ¾ million pictures. Even after going through all those pictures (twice to check for identification errors!) we still had lots of questions.

We deployed 497 multispecies bait stations in each of the colored 5x5 km cells from 2010-14.

Step 2 – Analyze the data and find out the results!

Analyzing our data and publishing our findings helped us to understand how to deploy bait stations in a multispecies framework and provide that information to other researchers.

The first thing we learned was that cameras detected more species (28 species) than DNA (14 species). DNA has a pretty solid reputation, so that might surprise you. But if you think about it, lots of animals (wolves and coyotes for example) are going to come take a look at that weird bait in the tree and not be able to climb up past the hair snares to take a bite.

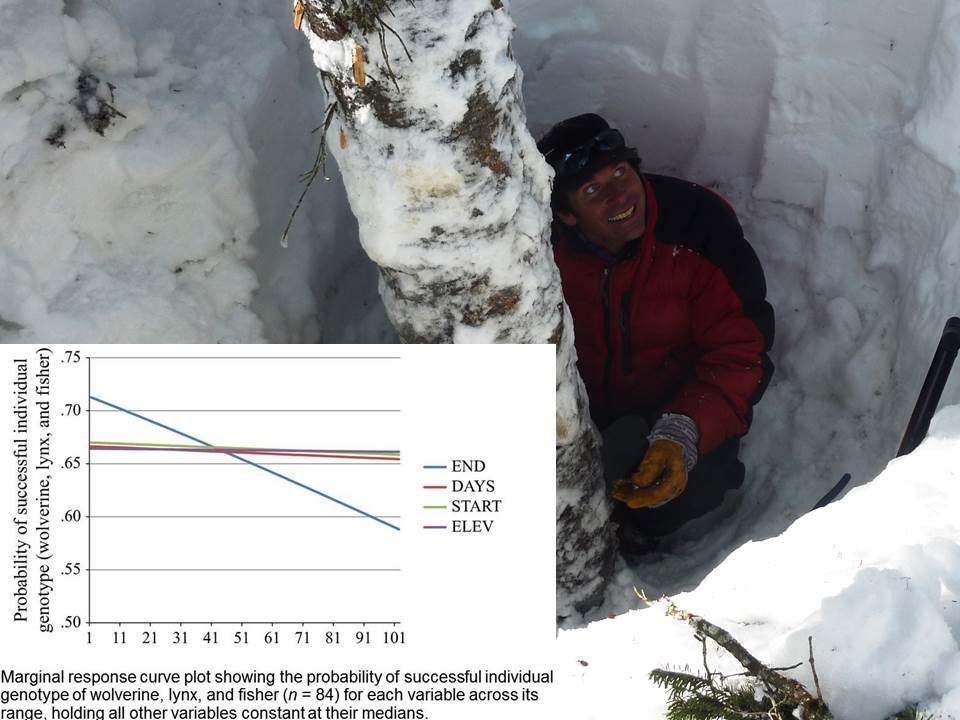

Despite detecting less species DNA is still important, and critical, if you want to identify individual animals. We wondered how long the DNA would stay viable when it was left out unprotected in the winter. The one variable we found that affected DNA quality was the date we took the station down. Some stations were not taken down until May or June and the DNA was probably degraded by the spring rains.

The DNA from the above buried bait station was fine. The graph shows that the date we took the station down is the one variable that contributed to DNA viability. Elevation, set up date, and deployment date did not matter. This means the DNA in exposed hair samples can survive a north Idaho winter until the rains come.

This is important to know because low-density species like Canada lynx and wolverines may take up to two months to detect. So we can rest assured our DNA from common species will remain solid while the stations wait for more rare species to come by. We also learned that quick to the bait marten and fisher were detected at the same rate across the winter season but bobcats and coyotes were detected much more often in late winter or early spring.

Step 3 – Use limited resources wisely

We tried ‘re-baiting’ some of our stations. A common practice in wildlife research is to do repeated surveys at the same location but, in this case, we did not find that to change our results. Basically, once a fisher or marten finds a tree with a beaver on it they stick around. Bringing another beaver…just keeps them there longer. So we determined the best use of resources is to put more bait stations in more places rather than to just keep resurveying the same spot

Using limited resources wisely is what this paper is all about.

Instead of doing a wolverine survey, then a fisher survey, then a marten survey….we figured out a way to combine them into a single survey effort. This wasn’t easy and we couldn’t have done it alone.

The field work required long days traversing north Idaho’s backcountry on snowmobiles and skis. The field work was a collaborative effort of the Coeur d’Alene Tribe of Indians, Kalispel Tribe of Indians, Idaho Conservation League, Idaho Department of Lands, Idaho Panhandle National Forest, and Selkirk Outdoor Leadership and Education. The Friends of Scotchman Peaks Wilderness harnessed 200 local volunteers that helped deploy bait stations.

Multi-species Baseline Initiative videos:

Citizen scientists and multi-species survey break new ground

Wildlife technician Scott Rulander explains the logistics of a day.