A research team concluded the walleye caught in Lake Cascade in May 2022 was not born in the reservoir and was illegally put there roughly 2 years before it was caught. Biologists compared the walleye’s chemical signatures with three perch that lived their entire lives in Lake Cascade to characterize the chemical signature of the lake. When they analyzed the walleye’s otolith (ear bone), they found it matched the chemical signature in Lake Cascade, but only for the past two years.

The walleye was second reported caught out of Lake Cascade in four years. https://idfg.idaho.gov/press/fg-confirms-second-report-walleye-caught-lake-cascade

Mike Thomas, Regional Fisheries Biologist in McCall, and his team need to know how many other walleye may be out there, and if they’re reproducing, which could change the Lake Cascade’s famous perch fishery and likely end the era of its famed “jumbo” perch that have made the reservoir a national destination for anglers.

Biologists are trying to learn where the walleye came from, and how long they’ve been in Lake Cascade. And they partnered with a team of research scientist to help get answers.

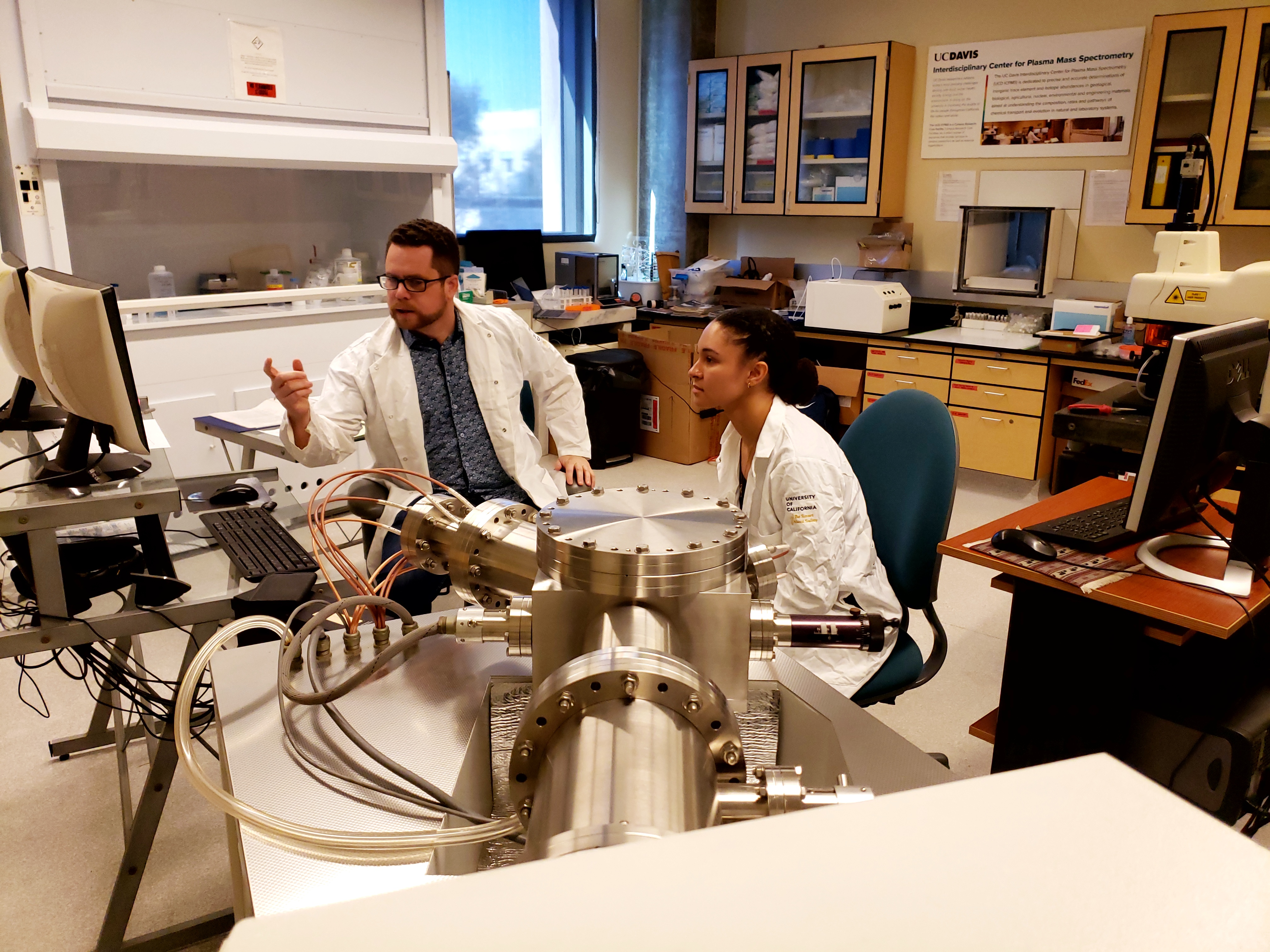

Thomas was fishing with friends in May 2022 when a friend caught the walleye. Luckily, Thomas was able to bring that fish back to the Fish and Game office in McCall to collect some samples and start searching for answers to some of their questions. The big question the team immediately focused on was whether or not this fish was born in Lake Cascade. To answer that question, the team took the otoliths (inner ear bones) from the walleye and sent them to a research team from NOAA Fisheries, UC Santa Cruz, and UC Davis Center for Watershed Sciences in California who specialize in using information recorded in otoliths to answer many types of questions in fisheries.

Otolith microchemistry analysis

When fish grow throughout their life, their otoliths grow too (just like our bones). Many anglers are aware that biologists can count the rings in an otolith to determine the age of a fish – just like with rings on a tree trunk. Perhaps less commonly known is that, as the otolith is growing, the chemical signature of the water in which they are growing gets incorporated into the bone.