For the first time since the early 1990’s, Fish and Game has collars on white-tailed deer in game management unit 1 in northern Idaho. Biologists use GPS collars to better understand deer movement and survival, answering the call from hunters for more data on one of the Panhandle’s most popular and accessible big game species.

Early collar data revealed the movements of does getting ready to give birth. While most does in the study stayed close to where they were collared, some traveled many miles to have their fawns, often within a few days of one another during May.

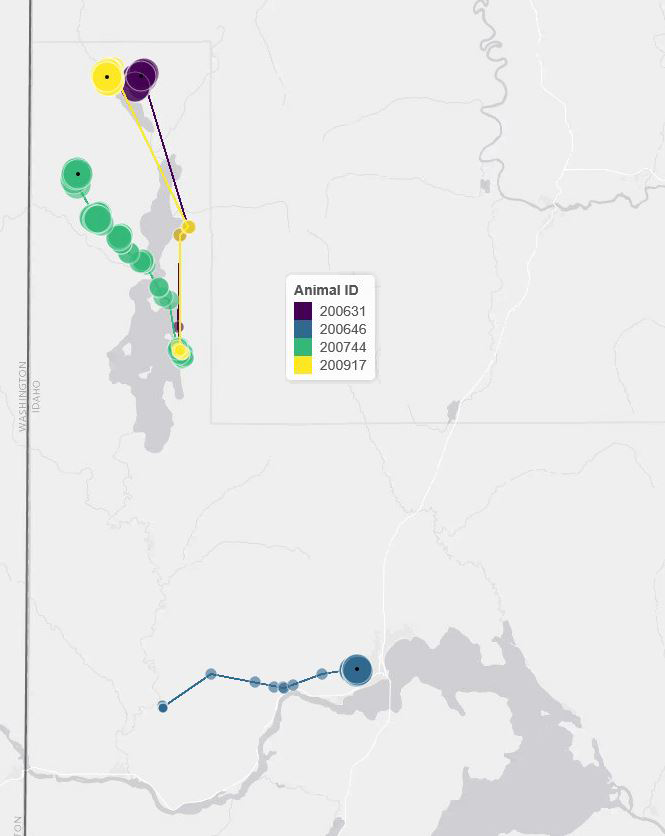

Doe number 200744 was collared near Hunt Creek on the east side of Priest Lake. On May 16, she began to head north then west, swimming across Priest Lake to eventually end up in the Granite Creek watershed.

Does 200631 and 200917 made two of the largest movements in the dataset, traveling over 20 miles in two days. They began their journey from Hunt Creek together then split off, one heading for Upper Priest River and one settling down near Trapper Creek.

Another doe was collared north of the town of Priest River in the Crazy Creek drainage. This deer traversed up and over the Selkirk Mountains to give birth near Sandpoint.

Biologists can only speculate on the reason these does made their journeys. “It’s a costly energetic move to travel that far right before giving birth.” said regional wildlife manager Micah Ellstrom. Typical fawning habitat contains quality forage, water and security cover in a relatively small area so does don’t have to wander far from their young to get what they need.

A total of 140 white-tailed deer were collared in game management units 1, 6 and 10A. Biologists have also collared elk, moose, mule deer, mountain lions, black bears, and wolves to get an integrated picture of the large mammal community in northern Idaho.

“We’ll be able to follow these deer from spring through winter, getting a much better understanding of what our deer need to successfully survive and reproduce and what their main causes of mortality might be,” said Ellstrom

Good intentions can undo moms’ hard work

The majority of fawns and calves are born in May and June in the Panhandle. Most does started their movements to fawning habitat within a couple days of one another.

During early summer, many concerned citizens call Fish and Game reporting orphaned animals. Most of the time, these animals are not orphaned at all and moving them can separate mother from offspring.

“The best thing you can do for those young animals is leave them be. The mother is usually nearby,” says Ellstrom. Leaving food out is highly discouraged as feeding deer can also attract predators and accelerates the spread of disease.

CWD preparedness

Disease is a major concern for Ellstrom since Chronic Wasting Disease was detected in nearby Libby, Montana in 2019. CWD is a fatal disease that affects deer, elk and moose. So far, it has not been detected in Idaho.

Collar data allows biologists to determine the cause of death for individual deer, deciphering between disease, predators, or malnutrition. If a deer from the study dies, its lymph nodes are tested for CWD. Knowing typical deer home range size and movement patterns from collars can help inform CWD response if the disease is ever detected in Idaho.

“We’ve seen some very interesting and impressive movements even within our first few months of monitoring collared deer and will be better prepared to manage this population,” said Ellstrom.

More information on Idaho’s Chronic Wasting Disease strategy is available on idfg.idaho.gov.