Salmon are the marathon runners — well, swimmers — of the fish world, and for some, their finish line is the rivers and streams of Idaho.

There are three species that make Idaho their final destination: Chinook, sockeye and coho. (If you really want to split hairs, you could add in kokanee salmon as the fourth, but technically they are the landlocked cousins of the sockeye family tree and don’t travel out to sea.)

Idaho salmon have similar life cycles that begin as a small, pinkish-orange egg laid in gravel nests. The females will use their tails like garden trowels to dig out little nests known as redds. Redds of Chinook salmon have been known to be up to four feet deep.

The males have a slightly different role in the process. They will spend their time gently nuzzling the females into laying eggs. Once the time is right and the salmon do their thing, they prepare for the final step in the process: death.

Now, as morbid as it sounds, their death isn’t instantaneous. The male and female will ensure the eggs are well protected under a fine layer of gravel, then await their final chapter.

‘We are born and we die’

For Idaho salmon, the journey of life begins and ends in the same place: freshwater. Chinook, coho and sockeye are anadromous species, meaning they hatch in freshwater, head out to the ocean to grow and then swim back up rivers and streams into freshwater to spawn.

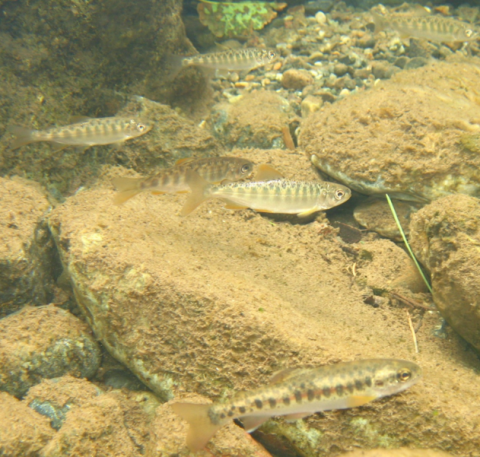

When salmon are hatched from the egg, they are called “alevins” and undergo several changes until they grow and become “smolts,” for their long journey – up to 900 miles –from Idaho’s rivers to the Pacific.

During their journey, the smolts methodically record changes in the water’s chemical composition by using their impressive sense of smell. They later rely on this information to build a mental rivermap that guides them back to their spawning grounds 1-4 years in the future. Imagine walking along the highway from Stanley all the way to Bakersfield, California, with only your nose for guidance. Good luck.

After some time in the ocean — typically two years, but it can range from one to five years — the matured salmon are ready to head back towards the mainland. Once they leave the salty waters of the Pacific, they won’t eat ever again. Relying on their fat stores, the Idaho-bound salmon travel back up main river channels into smaller and smaller tributaries until they reach the place they were born. That is, if they remembered correctly — not all salmon are successful at pin-pointing their birthplace.

And just like that, we’re back to the start. But that, by no means, is the end of the salmon’s story. There are countless other interesting facts about these incredible fish’s lives that you can read for yourself in this month’s edition of Wildlife Express.

Go to Idaho Fish and Game’s website and check out the Wildlife Express webpage under the Education tab for more information.