Steelhead fisheries in Idaho are world class, and the fact that anglers can fish for steelhead from July through April means there is lots of time to enjoy this resource. The fact that we can enjoy these long fishing seasons is due in part to Idaho’s hatchery program that produces lots of fish for anglers to catch and keep.

But the state also holds some of the best wild steelhead habitat in the Pacific Northwest, and wild steelhead provide an interesting glimpse into how their life histories evolved to suit their habitat and ensure they are able to make the arduous journey to the ocean and back to Idaho’s spawning streams.

Wild steelhead spawn and rear in a diversity of habitats across the state ranging from wilderness rivers, such as the Selway and Middle Fork Salmon, to small streams running through backyards and behind the gas station in rural areas. It’s been said that if there’s water running in a stream during spring in steelhead country, a steelhead will find a way to spawn there.

It’s only been in the past 10 years that Fish and Game biologists have started to understand what these wild populations look like in different parts of the state. This picture became even clearer in the last five years as biologists collected data from steelhead passing through Lower Granite Dam while going to and coming from the ocean and into rivers in Idaho, Oregon and Washington.

Each year, crews working at Lower Granite Dam trap adult steelhead as they swim up the fish ladder. Crews take a genetic and scale sample to learn their age and where they are likely to spawn. These fish are also implanted with tiny PIT-tags, which allow fisheries managers to track movements of individual fish as they swim over PIT-tag detectors located in many rivers and streams.

Fish and Game biologists use this date to better understand the diversity of Idaho’s wild steelhead and those in neighboring states.

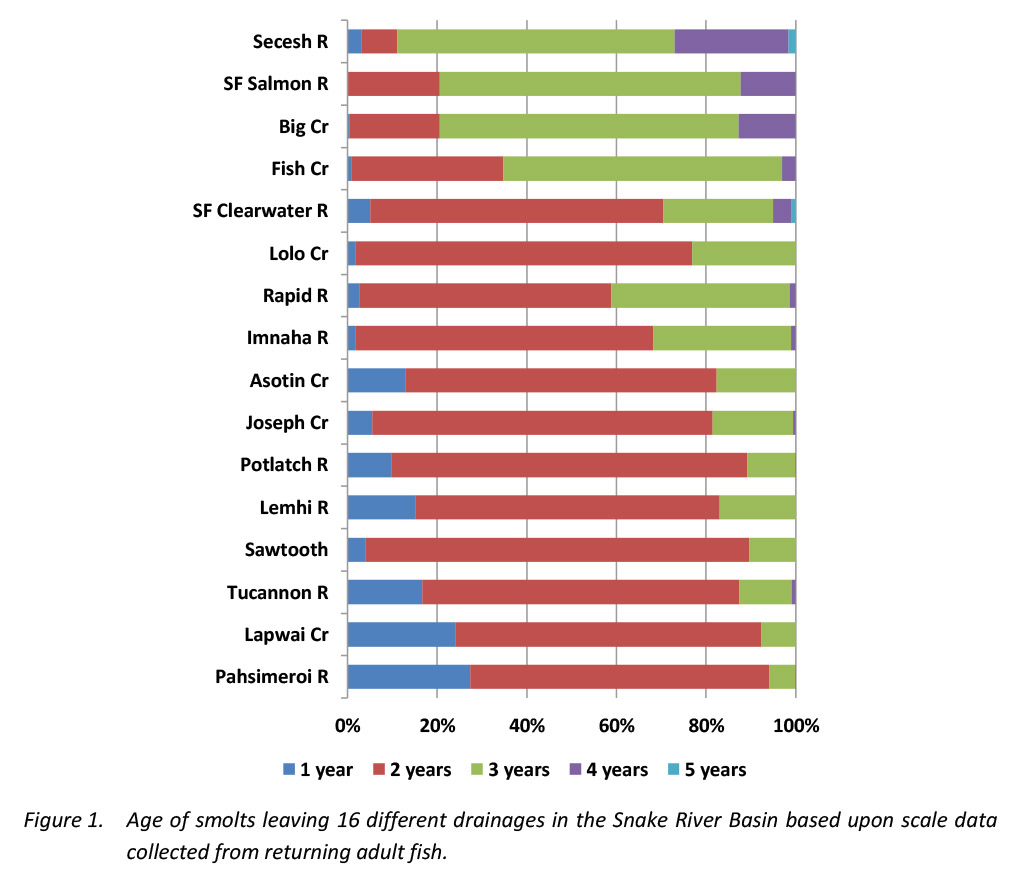

Depending on the stream, juvenile steelhead spend different amounts of time in fresh water before migrating to the ocean. All of Idaho’s hatchery steelhead are reared for one year and released to migrate to the ocean, but wild steelhead are very different.

Idaho steelhead can rear in the freshwater for one to five years before going to the ocean. In general, most populations are dominated by a two-year old smolts. Some high-elevations streams, such as Fish Creek, (a tributary of the Lochsa River), South Fork of the Salmon River, and Big Creek (a tributary of the Middle Fork of the Salmon River) are dominated by older smolts, mostly three-year olds. But each drainage has, at least three different age classes of smolts leaving each year.

Each color in this table represents a different life history of steelhead in the listed watersheds. Blue lines indicated what percent of fish stayed in freshwater for one year prior to going to the ocean; red lines indicate what percent stayed for two years and so on.

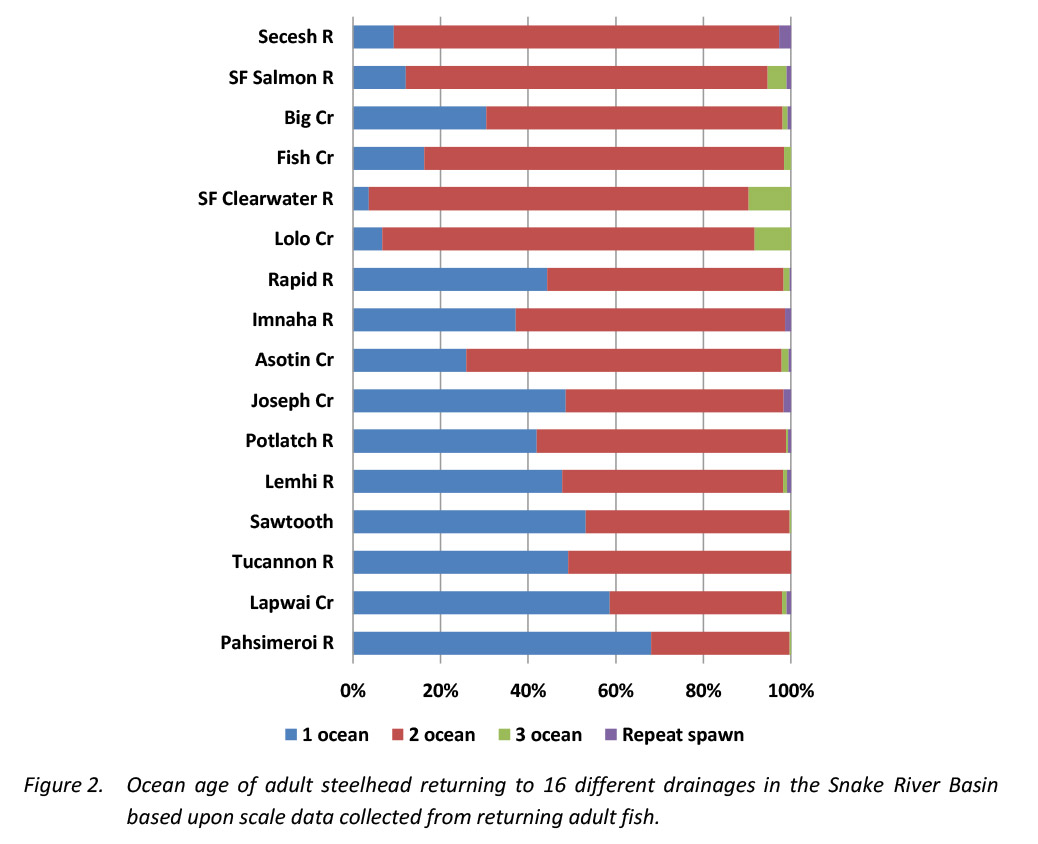

How long do these fish spend in the ocean? Is there consistency? If they swim to the same ocean, they should look pretty similar when they return to fresh water, right?

Not quite. There’s diversity among fish in different rivers, too, and even fish that return to the same rivers.

With adult fish, ocean time ranges from one to three years, and drainages are either dominated by fish that spend one or two years in the ocean. These are commonly known as “A” run and “B” run fish, but it’s not that simple because not all the fish labeled as either A or B behave the same.

Drainages in the lower Clearwater, lower Snake, and upper Salmon rivers are dominated by adults that spend one year in the ocean.

Drainages in the upper Clearwater and mid-Salmon river drainages are dominated by two-ocean adults. Also, more than half of the drainages listed above also have three-ocean fish. So again, similar to the juvenile ages, there are some general trends, but steelhead are diverse.

These rivers and the steelhead that occupy them are all a bit different and steelhead populations use this diverse life history to make sure that if one group doesn’t survive well, another group will. It’s how nature ensures the continuation of steelhead runs by spreading the risk so if part of the population is less successful, another can fill the void.

Wild steelhead have lots of strategies to help them be successful and make future generations. By understanding what they do in the wild, Fish and Game can better manage, protect, and restore these fish and the many habitats they occupy.