Can We Get Juvenile White Sturgeon To Grow Faster?

By Nolan Smith and Joe DuPont

Fisheries personnel for the Idaho Department of Fish and Game and Idaho Power were recently working in the Hells Canyon portion of the Snake River kicking off a new pilot study to better understand growth rates and movement patterns of juvenile White Sturgeon.

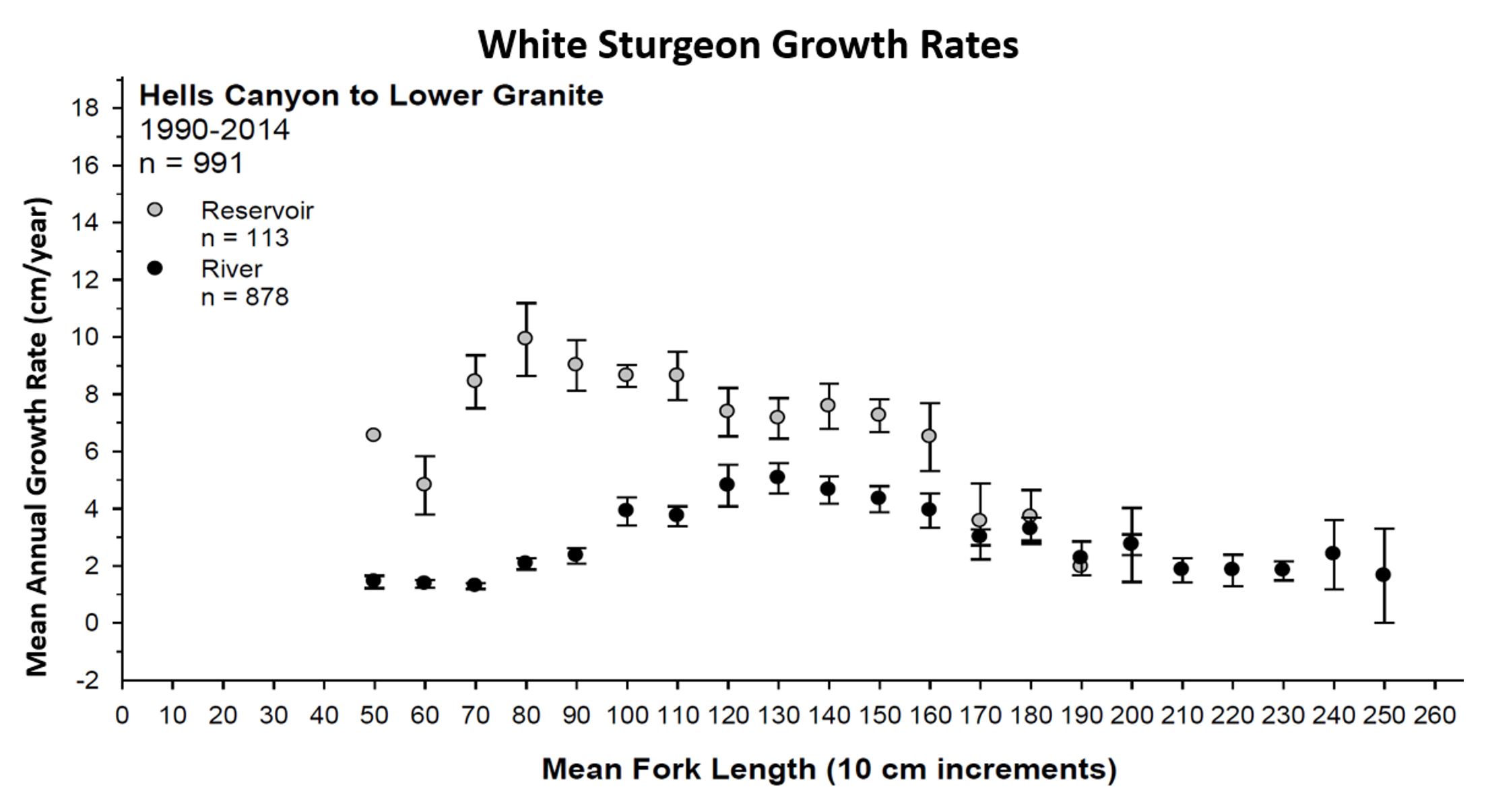

Past studies of White Sturgeon living in the Snake River between Hells Canyon Dam and Lower Granite Dam have taught us some very interesting and unique things about this population. For example, there are dramatic growth rate differences between juveniles living in the reservoir created by Lower Granite Dam and those living in the free flowing river in Hells Canyon. Sturgeon living in the reservoir that are less than 40 inches (100 cm) in length grow at an annual rate of around two to four inches per year, whereas sturgeon of similar sizes in Hells Canyon grow on average less than one inch per year! After exceeding this 40-inch threshold, the growth rate of sturgeon in Hells Canyon steadily increases to where it is similar to what is seen in the Reservoir. These growth rate differences are shown in the figure below.

Based on the growth rates of sturgeon that live in Hells Canyon, it will take them around 50 years to reach 7 feet in length, the size when females first start spawning! Additionally, based on fish we have tagged and recapture, we have learned that many juvenile sturgeon in Hells Canyon will remain in the same pool for 20 or more years. This means that many sturgeon living in Hells Canyon will not live long enough to reach spawning size, or if they do, the number of times they do spawn will be greatly reduced in comparison to those that live a portion of their life in the reservoir.

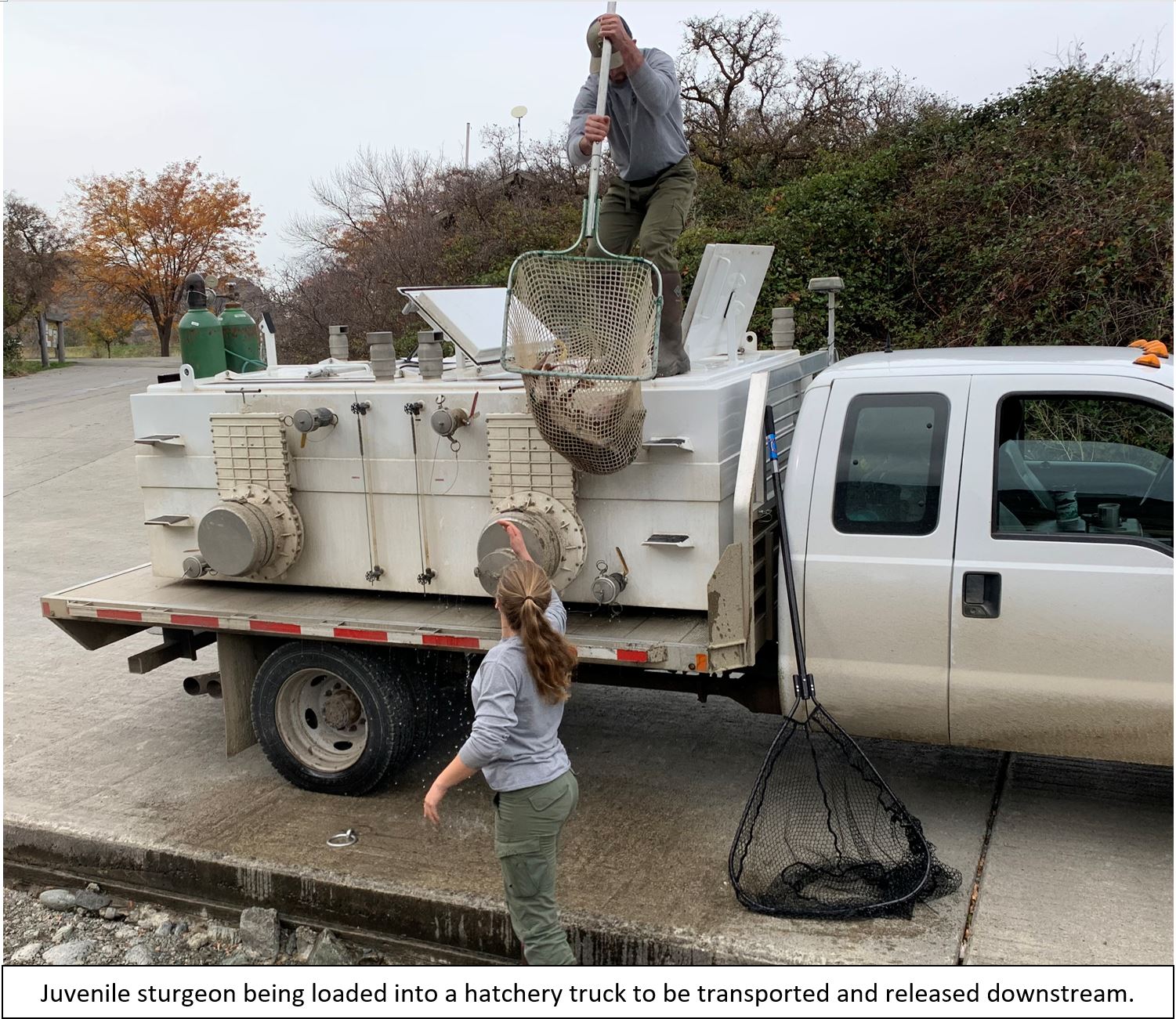

This pilot study was developed to evaluate whether we could move slow-growing fish from Hells Canyon to the reservoir where growth rates are much higher. Our hope are that these fish will remain in the reservoir long enough to grow through the bottleneck (past 40 inches). If this works, we believe we could use this strategy to increase the number of sturgeon in this population that reach spawning size.

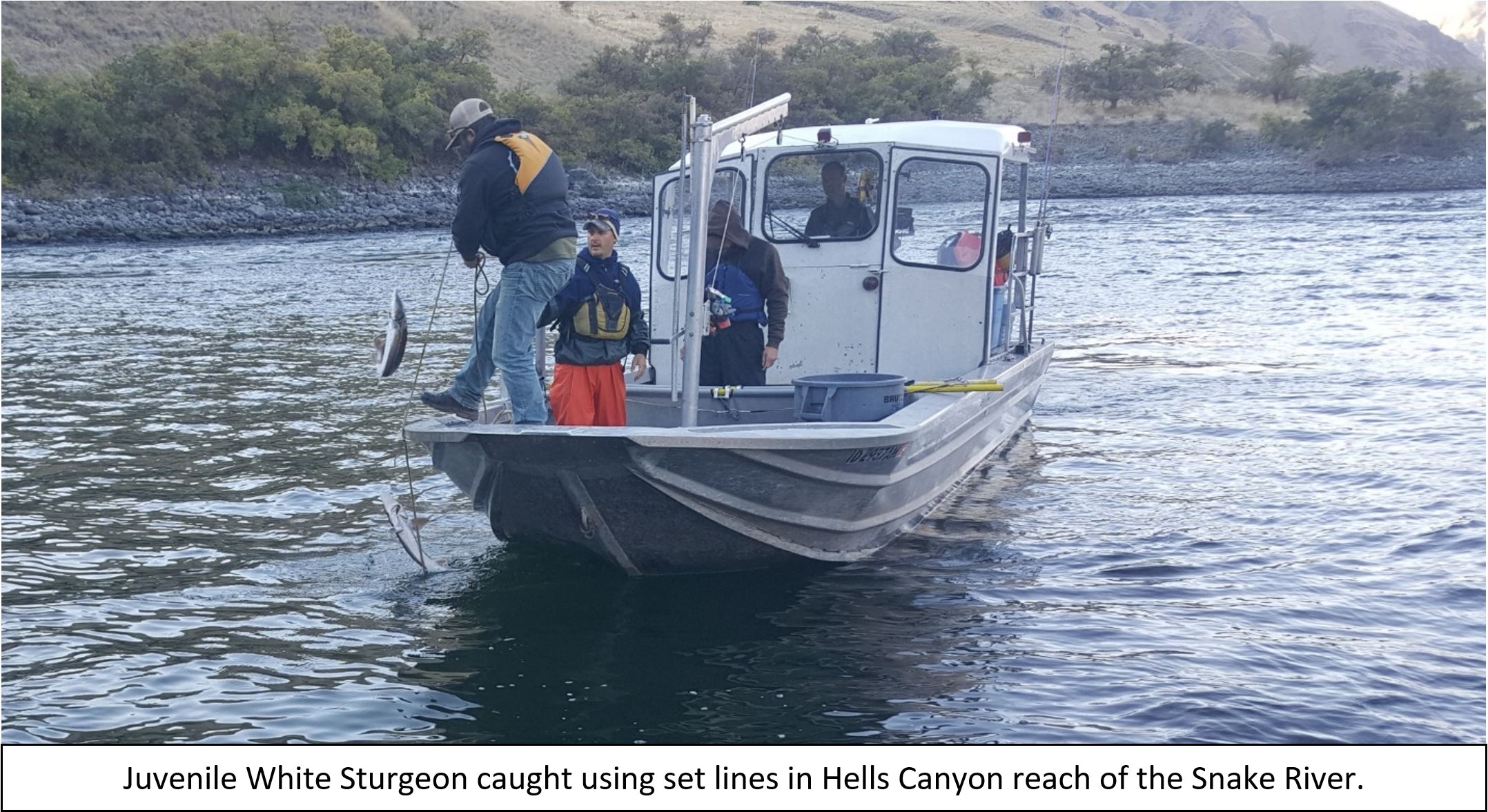

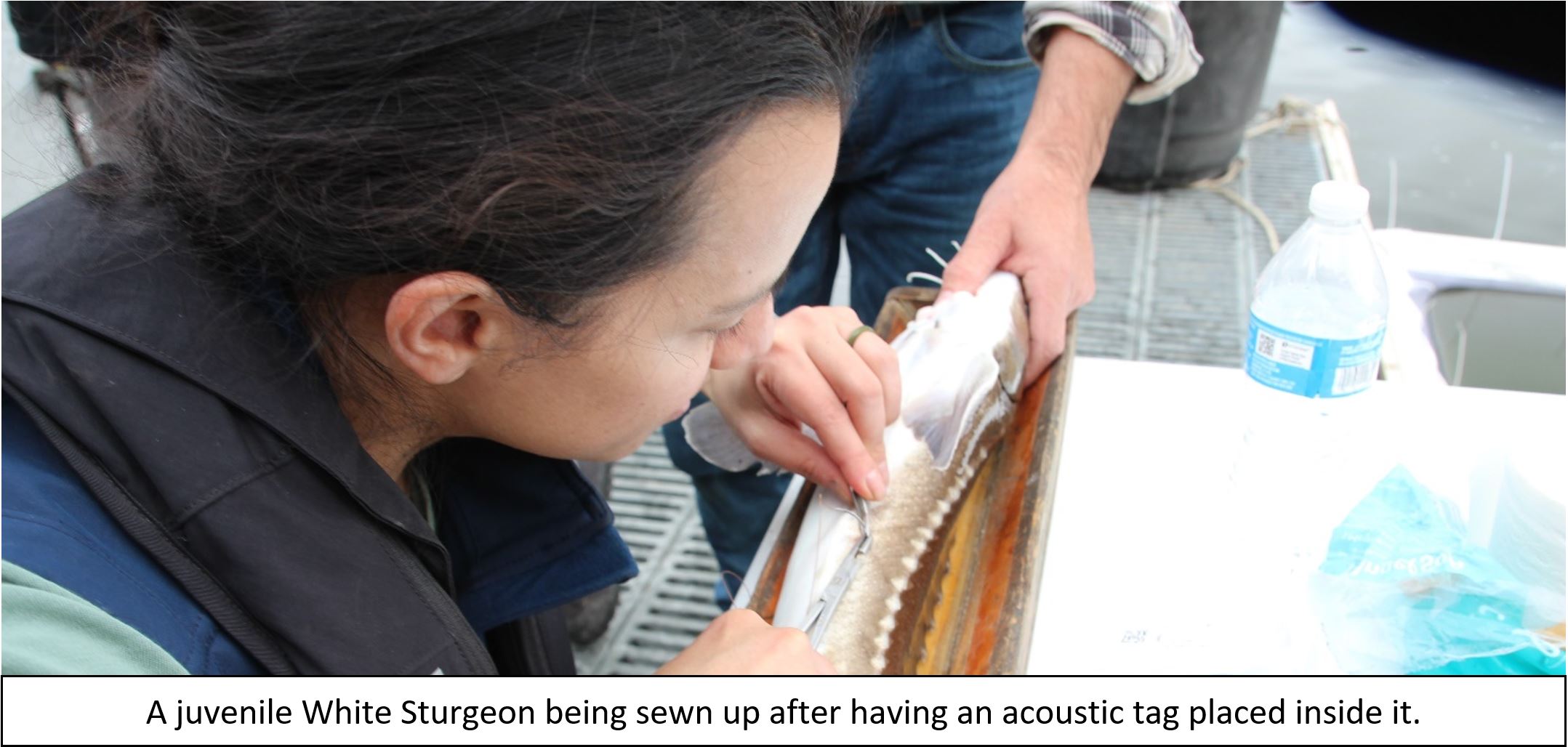

To help answer these questions, juvenile sturgeon were captured using both set lines and rod-and-reel from three pools upstream of Pittsburg Landing that were known to have high densities of juvenile sturgeon in them. These fish were then transported about 100 miles downstream and released in the reservoir about 13 miles downstream of Lewiston. All sturgeon were tagged with Passive Integrated Transponders (PIT) tags, which will allow us to determine if their growth rates changed when they are recaptured. In order to track the movement patterns of translocated fish, a portion of the captured fish were also tagged with acoustic telemetry tags.

All told, we captured 80 juvenile sturgeon over a three-day period. Fifty-five of the captured fish were transported down to the reservoir, 42 of which were tagged with acoustic transmitters. Additionally, there were 25 fish that were PIT tagged and released back to where we captured them to see if reducing the density of sturgeon in these pools will lead to increased growth rates.

We have already seen some interesting observations during the initial phase of this study to share with you. Because many fish captured in this study were previously PIT-tagged during other surveys, we are able to look at growth rates for fish dating back to the 1990’s. For instance, five fish we caught were originally captured and tagged in the same pools over 20 years ago and had an average annual growth rate of one-tenth of an inch! That means, if these fish do not move out of these high-density pools, they will never make it to spawning size. It also appears that there are differences in growth rates between the pools that we captured fish from. Not too surprising, we saw the slowest growth rates in those pools with the highest sturgeon densities.

These previously tagged fish also revealed information about migration patterns. One of the fish we captured was originally tagged in Lower Granite Reservoir and in a matter of one year migrated over 80 miles upstream into Hells Canyon. This fish has now been translocated back downriver, so it will be interesting to find out if will it move back up into the river or stay in the reservoir where growth rates are far greater. Time will only tell! We have already seen one of the other translocated fish move downstream through the juvenile bypass system at Lower Granite Dam. The movement patterns and growth rates of these fish are fascinating, and this pilot study will help shed light on how we can best manage this sturgeon population.