A long-term study from Brownlee Reservoir, conducted by Idaho Fish and Game and Idaho Power biologists, has shed some light on what makes crappie fishing good or bad at this popular Southwest Idaho reservoir. Survival of young fish appears to drive the population more than angler harvest, or other factors that can be controlled by fisheries managers.

Limited management options for sustaining large crappie populations

Crappie populations throughout North America are notoriously difficult for biologists to manage because their populations vary so much. With good reproduction, fishing can be tremendous for several years in a row and average fish size increasing each year until anglers are giddy with excitement. But other times, crappie populations can go years without good reproduction, resulting in years of frustration while anglers wait for fishing to improve.

Experiencing these up-and-down cycles makes anglers wonder why crappie fishing is so sporadic, and why fisheries managers can’t prevent the down years from happening? Research in the eastern U.S. has shown that crappie populations are affected by weather and water conditions that are beyond the control of fisheries managers. Studies have also indicated that factors affecting crappie in one lake may not have the same influence on crappie in another. But no studies have been done in western North America where crappie live in reservoirs that are quite different than natural lakes in the Midwest, or reservoirs in the South.

Crappie anglers enjoying a successful day of fishing on Brownlee Reservoir.

Why are they cyclic in Brownlee?

A long-term study at Brownlee Reservoir conducted by Idaho Fish and Game and Idaho Power biologists has shed light on what makes crappie fishing good or bad at this popular reservoir. Since 1993, biologists have surveyed crappie most summers with a trawling net to evaluate the annual numbers of baby fish (“larval fish”) just after they hatch, when they are less than one-inch long. To collect older fish, biologists used electrofishing to catch crappie in spring and fall.

Idaho Fish and Game staff trawl by towing a surface net to catch larval crappie in the summer at night to monitor their abundance in Brownlee Reservoir, and above is a sample catch from one net tow.

If you’ve fished Brownlee over the years, you may have a sense of some of the things the biologists found. Cycles of high and low crappie numbers were evident in both the larval trawling catch, and the spring and autumn electrofishing catch. It was also clear that if lots of small crappie were produced, they almost always provided good fishing for several years. But, if few young fish were collected, there were very few larger fish the next few years. That’s not really a surprise, but the question is: what causes those boom years when young crappie were so abundant?

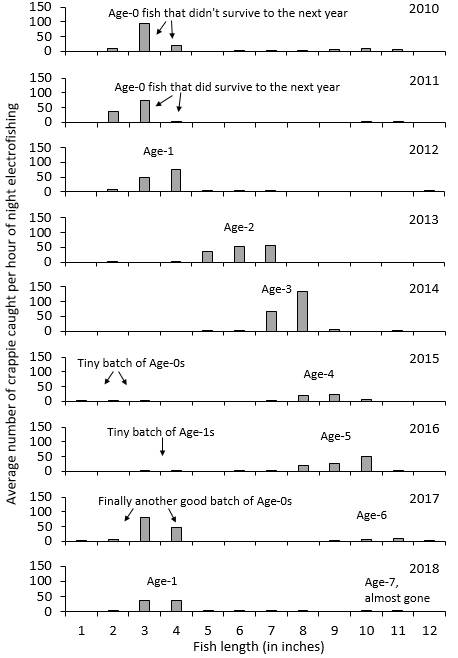

Several years of crappie electrofishing catch at Brownlee Reservoir shows how rare it can be for a good year of young crappie to be produced, how long it takes to grow big, and how long they stay in the fishery.

Survive and thrive

In the study, biologists found that none of the usual factors - like reservoir volume, inflow/outflow out of the reservoir, water temperature, and the number of spawning-sized crappie - seemed to affect the number of larval crappies in the summer. By the fall, however, some patterns began to emerge. Years with both high flows and a high abundance of larval crappie in the summer resulted in more young fish in the fall. Also, survival of young crappie over the winter was higher when they were larger and when reservoir level was higher.

Adding another layer of complexity, young crappie tended to grow faster in the summer when they were less abundant, probably because they had less competition for food. So, there may be a sweet spot for survival when young crappie are abundant, but not too abundant. Regardless, if a new group of crappie made it through their first winter, they almost always lasted for several more years, creating a good fishery by the time they reached two years, which in Brownlee means age 2 crappie are about 7 inches at the start of the year and about 8 inches at the end of that year.

Are anglers contributing to the down years?

A common scapegoat – angler harvest – does not affect crappie abundance in Brownlee Reservoir. Based on several years of data, anglers typically harvest 20 to 30 percent of the crappie population in Brownlee. That’s just not high enough to negatively influence such panfish populations. About 30 to 40 percent of crappies die off each year from natural, meaning they die at relatively high rates from natural causes, whether anglers harvest them or not.

For most panfish, angler harvest usually has to be higher than the natural mortality rate for harvest to reduce the numbers, or sizes, in the adult population. Another factor that doesn’t appear to affect crappie abundance at Brownlee Reservoir is smallmouth bass populations. Smallmouth bass in some reservoirs feed heavily on prey fish, including crappie, so when smallmouth bass are abundant, they can sometimes have a big impact on crappie abundance. But at Brownlee Reservoir, past research has shown that smallmouth bass feed mostly on zooplankton and invertebrates.

Enjoy the good years, wait out the bad ones because it will rebound

Fisheries managers can’t do much about water flow, temperature, or water levels in Brownlee Reservoir, and they can’t be entirely certain what creates big blooms of baby fish. Nevertheless, while it’s tough to tolerate several years of poor crappie fishing, it’s also nice to know that when the right conditions occur and lots of young crappie survive their first year, you can expect a bounty for years to come. And because crappie harvest isn’t a factor driving these cycles in Brownlee, anglers can continue to harvest what they can use without concern that they’re impacting the future of the fishery.

More to come regarding crappie fishing

Idaho Fish and Game has nearly completed a similar study at C.J. Strike Reservoir, where water management is drastically different from Brownlee. By next winter, biologists should have a much better idea of what is driving that crappie population, and fisheries managers will share the results of that research, too.