Anglers fishing for steelhead in the Snake River basin, particularly the Clearwater River, often hear the terms A-run, B-run or A-Index, B-Index steelhead but what exactly do those terms mean? The terms A and B are unique to steelhead management in the Columbia and Snake river basins and does not classify specific populations.

Rather the A and B terms define steelhead based on their adult size and the date they pass Bonneville Dam during their adult migration upstream. Snake River basin steelhead populations can be broadly termed “A-run” or “B-run” based on the dominant traits expressed. It is important to note that steelhead are extremely diverse, so there are overlaps in migration timing, age, and size across all summer-run steelhead populations in the Columbia River basin. To understand the reasoning for defining these two “types” of steelhead, we need to go downriver into the mainstem Columbia River and look at some history.

How did we get to the A’s and B’s?

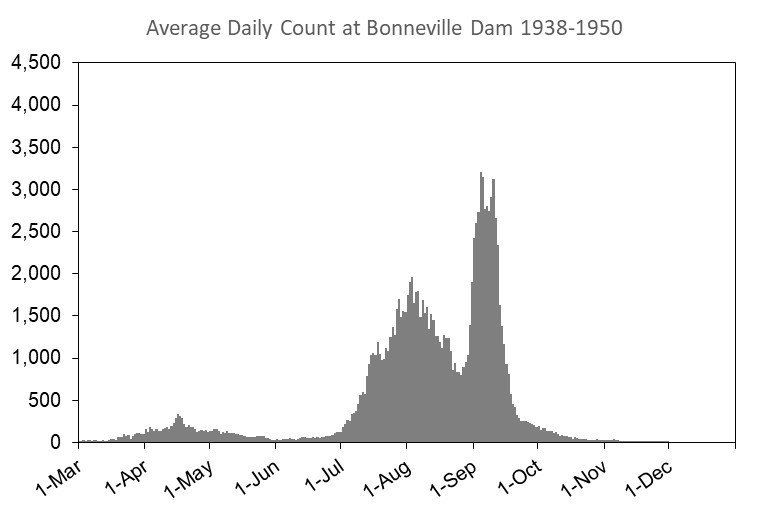

Looking at early Bonneville Dam counts of steelhead from 1938-1950 prior to construction of any other dams on the lower Columbia and Snake rivers and before the widespread stocking of hatchery fish, there were three distinct peaks of steelhead migration (Figure 1). The first peak was primarily winter steelhead that were migrating upriver during the late winter or early spring to spawn that same spring in tributaries to the lower Columbia River (hence the term “winter” steelhead).

The second and third peaks from July through October were labeled as summer-run steelhead as they crossed Bonneville Dam mostly in the summer. There is overlap in these two groups but generally, it was recognized that summer-run fish passing Bonneville dam after August 25 were different than ones that passed on or prior to that date. Typically, the later group were bigger in size and there was a fair certainty that most of these late summer-run steelhead were bound for Idaho.

Over time, a variety of changes occurred in the Columbia River basin that affected steelhead populations and their migration in the Columbia River. Big changes like the completion of The Dalles, John Day, McNary, Dworshak and the four lower Snake River dams, diminishing numbers of wild steelhead at Bonneville Dam, and increased hatchery returns from numerous summer-run steelhead programs all contributed to changes in the timing and abundance of steelhead observed at Bonneville Dam.

Dworshak National Fish Hatchery was completed in 1969 during the construction of Dworshak Dam and used wild fish returning to the North Fork Clearwater River as broodstock to ensure that those large steelhead would continue returning at similar levels as the wild population that would be extirpated. Because the wild North Fork Clearwater River steelhead were much bigger than steelhead from other Columbia River hatchery programs, they were first termed “B” steelhead.

The term “A” steelhead went to all other hatchery steelhead stocks. Meanwhile, steelhead bound for Idaho were drastically declining, and in 1974, Idaho closed steelhead fisheries for the first time ever to protect Dworshak Hatchery broodstock and wild populations. To further protect these unique Idaho wild and hatchery fish, Columbia River harvest in the 1970’s and 1980’s was initially managed using a date method at Bonneville Dam because of the historic distinction in run timing. Group A steelhead were defined as wild- or hatchery-origin steelhead passing Bonneville Dam between July 1 and August 25 and Group B steelhead were those wild- and hatchery-origin fish passing Bonneville Dam between August 26 and October 31. Bonneville Dam escapement goals were developed for wild summer-run Group A and Group B steelhead so that a certain amount of wild fish would be expected to pass Lower Granite Dam.

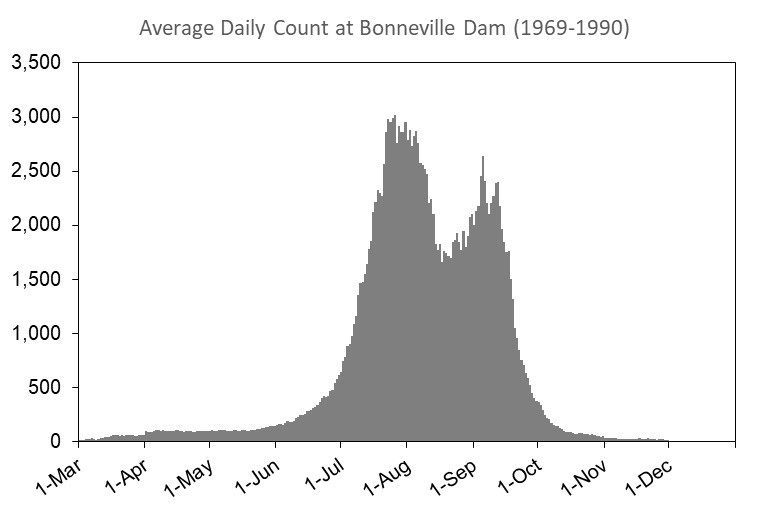

With the addition of several other hatchery programs in the Columbia and Snake River basins in the early 1980’s, hatchery-origin steelhead became more abundant than wild steelhead and the two distinct peaks in the summer run became obscure (Figure 2). The run timing of Dworshak hatchery steelhead and the late returning wild stocks that produce most of the large fish is similar to fall Chinook salmon, making them vulnerable to tribal fall Chinook salmon fisheries in the Columbia River. Due to the risks for Idaho steelhead that produce these large fish, fishery managers needed a better way than a date at Bonneville Dam to define A and B groups for downriver fisheries in the Columbia River. This also coincided with the drastic decline of wild steelhead in the Snake River basin that ultimately led to them being listed under the ESA in 1997.

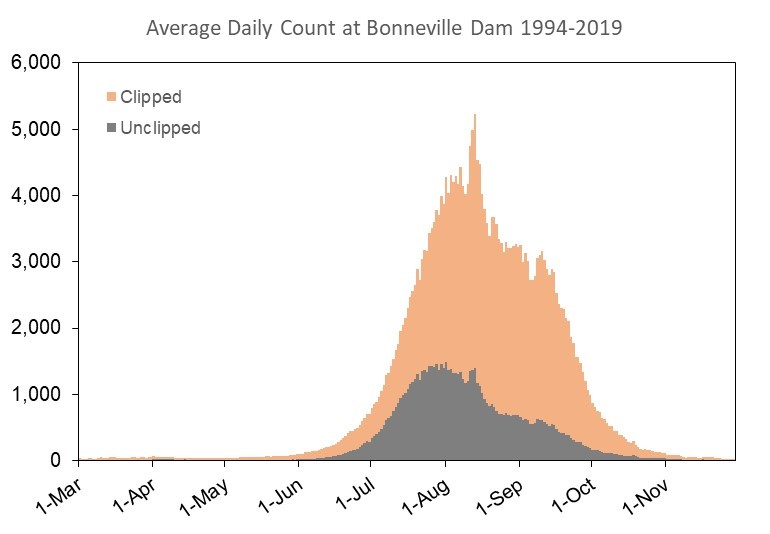

Fishery managers started using a date and length criteria or index method in 1999 to better manage summer-run steelhead fisheries in the Columbia River and protect large Idaho-bound steelhead. Group A-Index steelhead were defined as those wild- and hatchery-origin fish that pass Bonneville Dam between July 1 and October 31 that are less than 78 cm (31 in) fork length. Group B-Index steelhead were defined as those wild- and hatchery-origin fish that pass Bonneville Dam between July 1 and October 31 that are greater than or equal to 78 cm fork length. However, once steelhead enter the Snake River, the A-Index and B-Index designations are not used. Instead, incidental harvest impacts on wild steelhead are managed by major population group (Clearwater River, Salmon River, and Snake River) regardless of length or timing. Sometimes managers will use size classifications to manage steelhead in Idaho during years with low hatchery returns to ensure sufficient numbers of bigger, older steelhead can be collected for broodstock.

Why are some steelhead populations older and larger than others?

The North Fork Clearwater River is thought to have been the most productive drainage of larger, older steelhead in the Columbia River basin. The Dworshak Hatchery stock continues to be known for its big fish to this day. Many other wild steelhead areas in the Clearwater and Salmon river basins continue to produce larger, older fish. These systems tend to be in confined steep terrain and be cooler in temperature year round like the Lochsa, Selway, South Fork Clearwater, South Fork Salmon, and Middle Fork Salmon rivers. Because of the colder, less productive environment, these fish grow slower and are generally older (up to 5 years old) when they go to the ocean as smolts compared to many steelhead populations in the Columbia River basin. These fish stay in the ocean longer, so 2-ocean and 3-ocean fish are more common than in other populations. Their larger size is advantageous when returning back to these remote, rugged systems and is likely the reason they evolved to be bigger.

What we know today

Today, fish biologists and managers wouldn’t be able to use a date at Bonneville to effectively manage Idaho steelhead populations (Figure 3). Since these A and B designations were established, advances in genetic and PIT tag technology provide better tools in identifying and monitoring wild and hatchery steelhead stocks. There is also better understanding of life history diversity, and the range of characteristics such as age, size, and run timing that wild steelhead populations in the Columbia River basin can exhibit.

Big fish are not exclusive to Idaho. Steelhead are diverse and all populations have the potential to produce large and older fish; they are just more common in some populations. Current wild fish management and fishing regulations ensure protection of all life history strategies found in steelhead populations in Idaho. It’s important to remember that grouping steelhead arbitrarily by dates and size does not represent the full complexity and resilience of Idaho’s steelhead resource.

For more information on Idaho’s wild salmon and steelhead click here