In recent blog articles, you’ve learned about new fish detection systems being installed on rivers in Idaho and how managers use these systems to gain a snapshot of tagged fish in a particular place (read those blogs here and here). With more of these systems in place, managers can track and monitor the journey of anadromous fish, like the Chinook Salmon, with finer detail. This can even allow a single fish to be monitored from the time it was tagged, across the hundreds of miles to the ocean, through each of the 8 dams on the Columbia and Snake Rivers, and back as an adult. You will see one such journey below.

Fisheries biologists monitor this remarkable journey every year using a variety of tools. One important tool is a rotary screw trap (photo below). The Idaho Department of Fish and Game (IDFG) uses rotary screw traps to capture and tag wild juvenile Chinook Salmon and steelhead at over 15 locations throughout the state. By tagging juveniles captured at screw traps with PIT tags (passive integrated transponder tags) managers can track their movement on the way out to the ocean, and as they return as adults.

PIT tags (photo below) contain a small microchip that is read when passed by an antenna. Information associated with that tag are then uploaded to an internet database. Over one million juvenile fish are PIT tagged annually in the Columbia and Snake River Basins and there over 250 PIT tag antennas in these basins to read the tags, including antennas at each of the 8 dams Idaho fish cross on their way to and from the ocean.

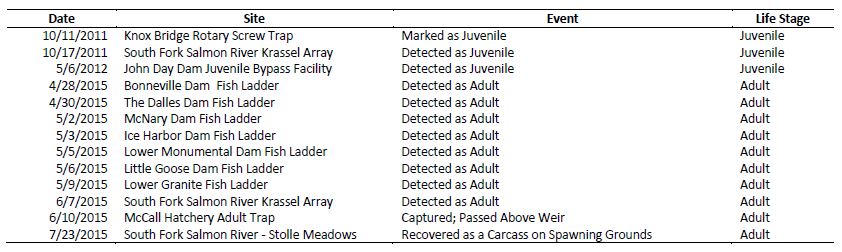

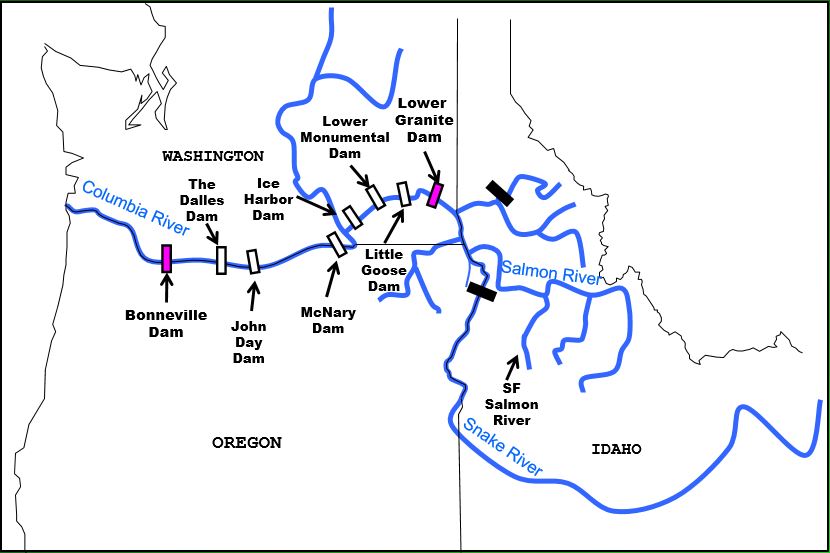

The table and map below are an example which highlights the long journey one wild salmon took after it was implanted with a PIT tag at a screw trap on the South Fork of the Salmon River in 2011. The table below lists notable detections of this tagged fish as it crossed PIT tag antennas on its way to the ocean and back.

After being tagged on the South Fork Salmon River in 2011, the fish headed into the Snake River and then into the Columbia River where it was detected at the John Day Dam on its way to the ocean in May 2012. While in the ocean, Idaho fish will swim as far away as Alaska before returning back to the mouth of the Columbia River to begin their migration back to Idaho. This particular fish stayed in the ocean for 3 years and was detected in the fish ladder at Bonneville Dam—the first dam on the fish’s journey back to Idaho—in April of 2015. The fish is then seen making its way through the 8 dams on its way back to Idaho, arriving at the final dam, Lower Granite Dam, 11 days later. Nearly a month passed before it was detected at the Krassel PIT tag antenna on the South Fork Salmon River, over 250 river miles upstream of the final dam. Three days later, the fish appeared at the fish trap on the South Fork Salmon River and was passed above the weir to spawn naturally. Two weeks after that, the fish was recovered as a carcass on the spawning grounds, having completed its life cycle. These locations can be seen on the map below.

Data like this are not only fascinating to visualize, but can be used in a number of practical ways. Information from PIT tagged juveniles can help managers determine survival rates downstream through the 8 dams, and PIT tagged adults give managers clues on how many wild fish are expected to return to various Idaho streams, travel times back up through the dams, and timing of arrival back in Idaho streams; all of which is essential for managing Chinook populations in Idaho.

For a fish, these migrations are instinct and a natural part of their life cycle. For fisheries biologists, monitoring these migrations are a necessary component to understand and manage populations. This whole process starts by tagging fish as juveniles at rotary screw traps, and watching the story unfold.