If you are planning to celebrate the New Year with a couple of beers you might have more in common with snails and slugs than you think. Idaho Fish and Game recently published a paper evaluating the best ways to do surveys for snails and slugs and, among other things, we tested the old gardening trick of using beer for bait. As is turned out, slugs really do like beer.

Unless we are looking for them we don’t tend see snails and slugs very often in northern Idaho. But we have a really rich community of about 60 species that are critical for forests to function well. Snails and slugs decompose leaf litter and logs and are important food sources for the birds and mammals we all know and love. They also are one of the more at risk species groups in the world and many are listed as Species of Greatest Conservation Need in Idaho's State Wildlife Action Plan. Trouble is we just don’t know much about them. In fact, until we did this study, we didn’t even know how to most efficiently look for them. To address this issue we did a large statistical analysis of nearly 1,000 gastropod surveys we conducted in Idaho, Washington, and Montana. Our goal was to figure out what worked, what didn’t, and summarize that information for others to use.

Effective conservation depends on knowing the status of the species we are trying to conserve. From 2010-14 we conducted a massive snail and slug survey in northern Idaho. We analyzed the best and worst ways to look for these animals and published our findings in the journal Ecosphere: Beer, Brains, and Brawn as Tools to Describe Terrestrial Gastropod Species Richness on a Montane Landscape.

Smokey taildroppers (left) are one of our more colorful slugs. They 'drop' a little piece of their tail when being pursued by predators such as robust lancetooths (right). This makes the predator stop to eat the tail piece while the potential prey gets away. When collecting gastropods in vials we have to be careful to keep lancetooths in their own vial or they will quickly eat all of the other snails and slugs we collect.

What We Did:

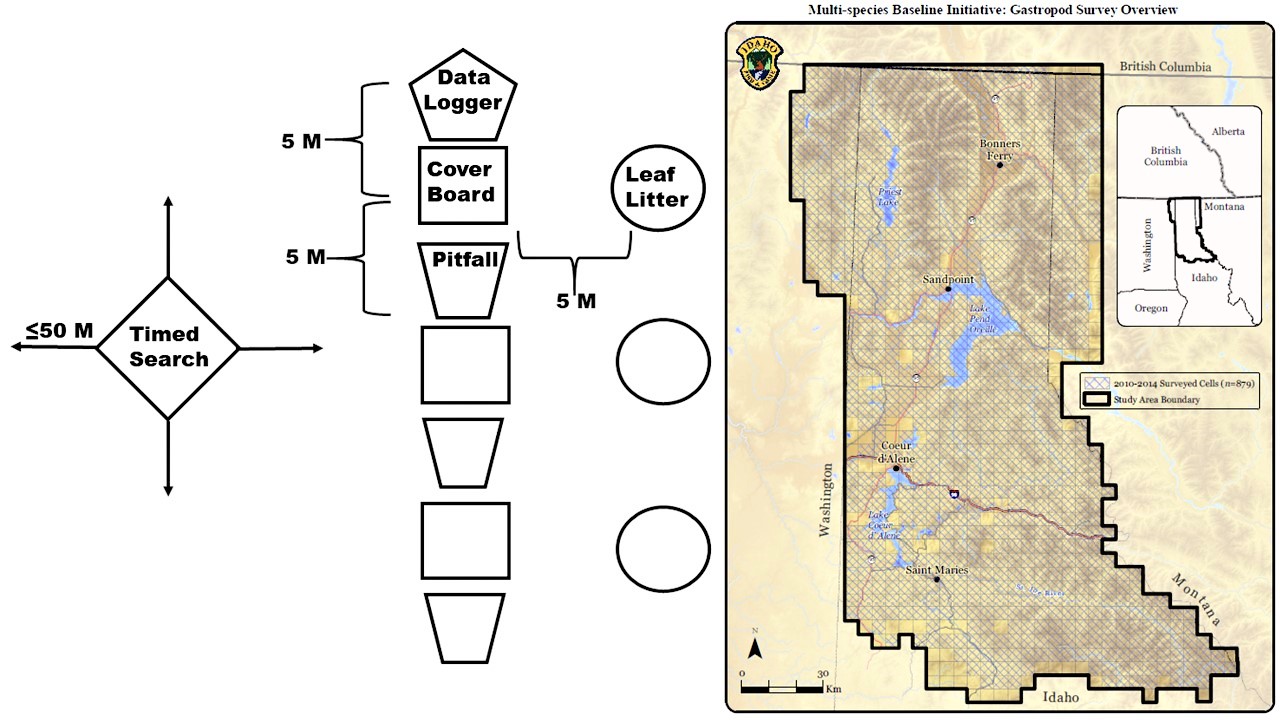

Several ways researches look for gastropods are to use cover board traps (square pieces of cardboard on the ground), visual searching (under rocks and logs), sorting through leaf litter (forest floor duff), and pitfall traps (plastic cups stuck in the ground). We fused all of these methods into a single survey transect and deployed these at 991 survey sites across a 14,000 square mile area. We experimented with baiting the cover boards by setting some out dry as controls, soaking some with water, and soaking some with beer. There has never been a study of this magnitude comparing these techniques.

From 2010-14 we deployed 991 gastropod survey transects in 879 5x5 square kilometer survey cells.

What We Found:

A combination of visual searching and sorting through leaf litter was the best way to find the most species with the least effort. We found most species just by visual searches, but there are some really tiny snails that we found almost exclusively in the leaf litter. The best time of year to do searches is early spring after the snow melts.

Cardboard cover board traps (left) are simply a piece of cardboard set out for a couple weeks then checked for gastropods hiding under or in it. Cover boards detected small slugs, like this pygmy slug (right), well and performed best when baited with beer. Overall, the cover board traps worked okay and beer worked much better than water as a bait. However, it probably would not be worth using traps again because it meant we had to travel to our remote sites multiple times.

Learning how to look for these animals was just a step in the process of our main mission to map out their distribution in our region. Data from this project showed that many gastropod species were more common than we thought and we were able to remove seven species from Idaho's Species of Greatest Conservation Need List.

We found magnum mantleslugs (above) for the first time in Idaho since 1948. They were well distributed across the study area but were very strongly associated with cool air, may be sensitive to climate change, and are still listed as a Tier 1 Species of Greatest Conservation Need in Idaho.

We found a new species, Skade’s jumping-slug (above), which also is found only in cooler than average locations.

Most species we found were more common than previously thought though. Fir pinwheel snails (above) were thought to be imperiled in Idaho but turned out to be the second most common species in our survey.

We now know we don’t need to focus our efforts on fir pinwheels but we definitely need to pay attention to magnum mantleslugs. We hope our findings help give others the tools they need to conduct similar surveys in other areas to implement the first step in conservation: to see what’s out there.