Written by Tiege Ulschmid, IDFG Fish Habitat Biologist

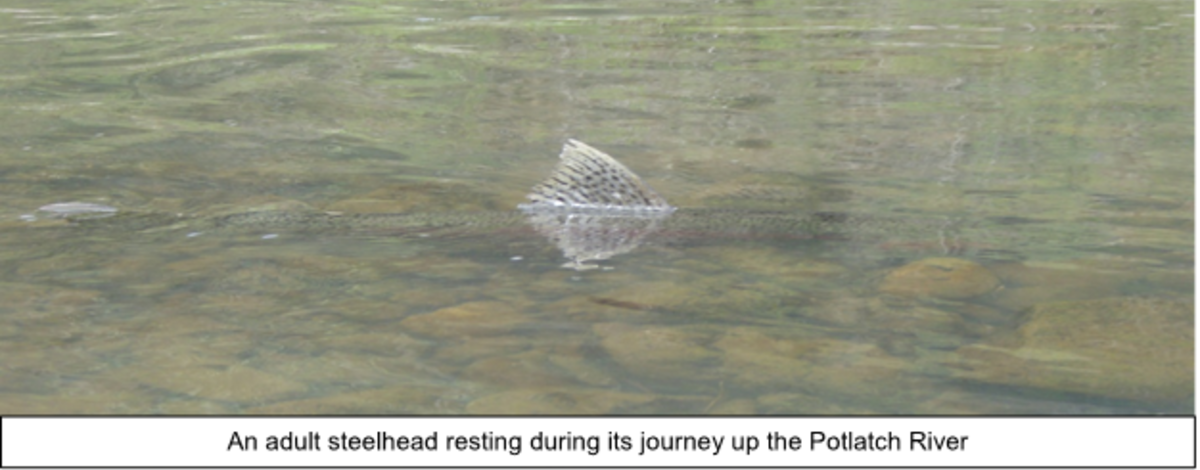

The Potlatch River was once a relatively unknown tributary of the Clearwater River. However, due to recent studies and restoration activities that have occurred in this watershed, people are becoming more aware of its importance. If you ask a steelhead angler now about the Potlatch River, many will tell you that this watershed has an important and unique run of wild steelhead that has the potential to grow and contribute greatly to Clearwater River basin’s overall wild steelhead population.

Idaho Department of Fish and Game (IDFG) fisheries biologists have been conducting research for more than 20 years on this steelhead population and now have a good understanding of what the needs of these fish are and what can be done to improve their survival. In general, researchers have found that increases in summer stream flow, improved access to spawning and rearing areas, and more instream structure will boost the number of steelhead that this watershed can support. With this understanding, we are working with landowners to chip away at these habitat limitations. As these restoration projects add up, steelhead returns to this watershed are expected to increase.

The IDFG just finished a steelhead habitat restoration project on the East Fork Potlatch River that we would like to share with you. The project occurred on U.S. Forest Service property on a reach of river that was altered near the turn of the century when it was being explored for logging purposes. At that time, railroads were the main means of exploring areas, and they were typically built alongside creeks and rivers. This reach of river was no exception, and the railroad bed that was constructed has effectively blocked the river off from its floodplain for about 100 years. On top of this, most of the trees alongside the stream were harvested, and any wood that remained in the stream channel was removed to reduce flooding and prevent damage to the railroad grade. With the channel being cleared of debris and confined by the railroad grade, the river generated a tremendous amount of energy during high flow periods. This increase in energy caused the river to down cut and turned it into something that looked more like a ditch then a steelhead stream. There was little in this reach of stream that would appeal to a juvenile steelhead. If you were an angler looking for a place to catch a fish, you would walk right by this area. Our fish surveys confirmed this as few juvenile steelhead were observed in this reach of river.

The goal of this project was to return large woody habitat to the stream and improve the river’s ability to access the floodplain. To accomplish this, we graded back 600 cubic yards of railroad berms to increase floodplain access, and ten large woody structures were constructed across ¼-mile reach of river. In this case, large wood meant big trees and logs that were anchored into the stream bank and jutted out into the river. These structures were designed to provide resting areas for adult steelhead, create deposits of spawning gravels, and provide summer and winter rearing habitat for juvenile steelhead. These woody structures were created from about 40 trees that we accessed from close to the river.

If you have never been involved in habitat restoration projects, they take a lot more planning and work than you may think. This project was dreamed up more than 3 years ago. From that point, multiple design reiterations occurred to help insure this project would provide the benefits to steelhead we desired. Before the designs could be implemented on the ground, funding had to be secured and the proper permits had to be acquired. Permitting included fulfilling the U.S. Forest Service’s NEPA process, receiving approval from NOAA Fisheries (they manage ESA listed salmon and steelhead), and acquiring a dredge and fill permit which included consultation with several state and federal agencies. Finally, a cultural review was required to ensure there would not be a negative impact on any potential historical artifacts of the area. The actual groundwork didn’t take much times, just 7 days. This is the fun and exciting part of the project, but still care had to occur to make sure fish were protected from instream work, sediment delivery to the stream was minimized, and the engineering design specifications were followed.

We are excited to have this project completed, but with more than 14 miles of degraded steelhead habitat to be restored, it will take some time before these types of projects start resulting in noticeable differences in steelhead returns. We are committed to the process and believe that over time these projects will add up to make a difference. This is completely dependent on getting buy in from landowners of course.