One of the first things Idaho’s spring and summer Chinook Salmon anglers want to know when they net their prized catch is whether it has an adipose fin or not. A clipped adipose fin with a healed scar means the angler can keep their trophy. An intact adipose fin and the angler must release their catch, often leaving them wondering about the iconic fish they just released. Where did it come from? How old is it? How many are there? Answers to many questions about wild salmon in Idaho lie in the data collected by Fish and Game and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) staff at Lower Granite Dam located about 40 miles downstream of the Washington/Idaho border.

Where the Wild Chinook Are

Learning the life story of Chinook Salmon at Lower Granite Dam

Dating back to the completion of Lower Granite Dam in 1973, an adult trap located on the fish ladder has been used to collect detailed information to supplement the window counts of adults that are ascending the ladder. This trap is operated systematically to sample a proportion of returning spring/summer Chinook to answer many of the questions anglers and fisheries managers have. As of July 2, there have been 58,011 spring/summer Chinook counted at the window on the Lower Granite fish ladder, and 10,265 of these fish were sampled at the adult fish trap of which roughly 16% have been wild based on the presence or absence of adipose clips and coded wire tags.

One of the most valuable samples collected at Lower Granite is a piece of fin tissue, about the size of an eraser head. With this fin tissue, we can evaluate the genetics and determine whether the fish was wild or not and where it most likely came from. Upstream of Lower Granite Dam there are five unique genetic stocks of spring/summer Chinook: Hells Canyon, South Fork Salmon River, Middle Fork Salmon River, Chamberlain Creek, and Upper Salmon River. The Hells Canyon stock is an aggregate genetic stock that includes naturally produced Chinook from the Clearwater, Little Salmon, Grande Ronde, Imnaha and lower Snake rivers. The first batch of 2023 fin tissue samples were analyzed earlier in June, and included every wild Chinook trapped and sampled through June 2nd. Through this early portion of the wild spring/summer Chinook run at Lower Granite, 56% assigned to the Hells Canyon stock, 19% to the Middle Fork Salmon River stock, 17% to the upper Salmon River stock, 7% to the South Fork Salmon River stock, and 1% to the Chamberlain Creek stock. This early sampling will be mostly represented by spring fish and fish arriving later in the season will be mostly summer fish, as such we expect the proportions of the Hells Canyon stock to decrease, and fish destined for areas in the Salmon River basin to increase.

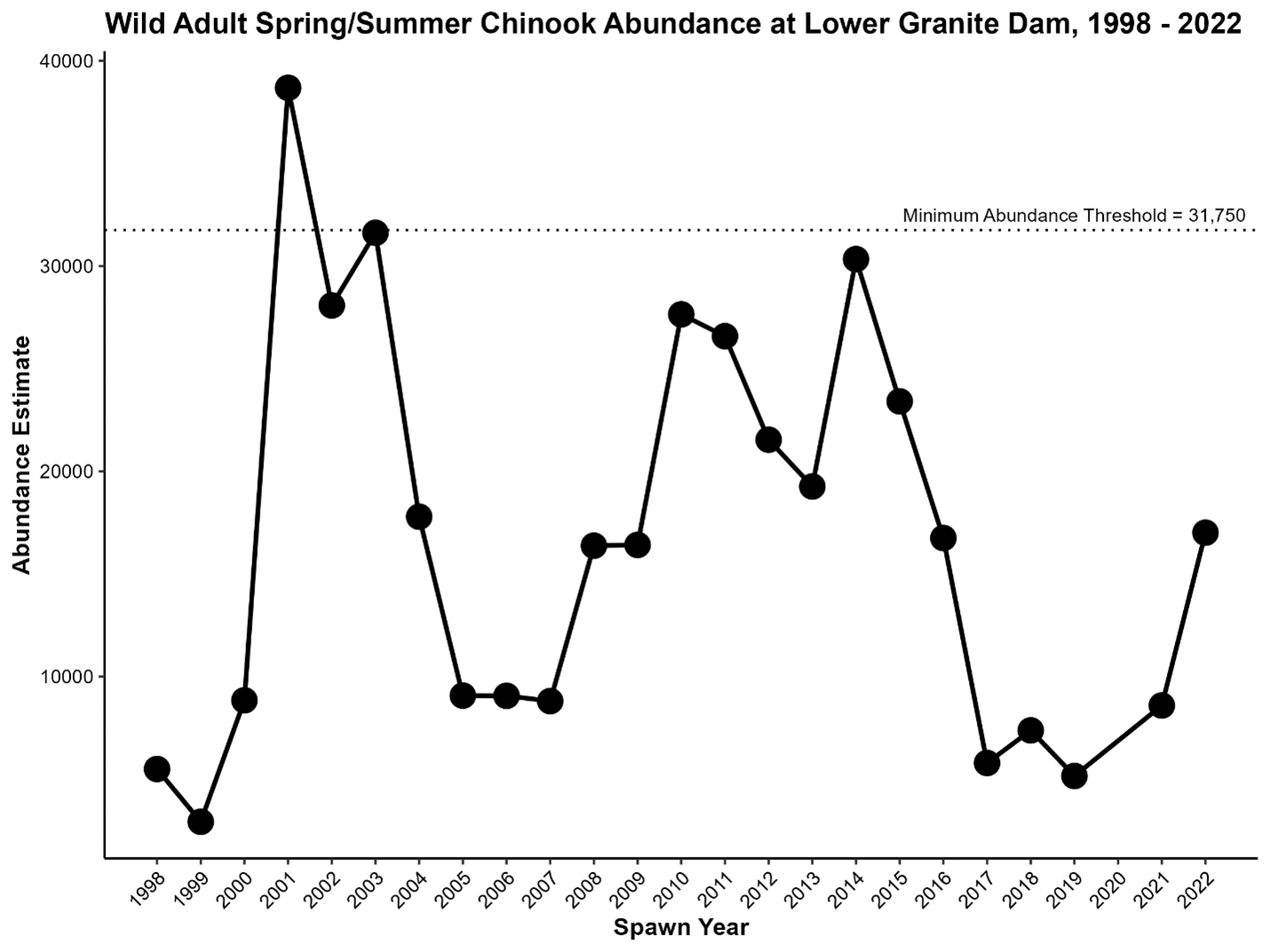

To give you a feel for how wild spring/summer Chinook Salmon returns past Lower Granite Dam have fluctuated since 1998, I put together the figure below. As you can see, wild returns picked up in 2022 (17,012), following five consecutive returns (2017 – 2021) that were below 10,000 fish. However, wild escapement above Lower Granite Dam in 2022 was still well below NOAAs minimum abundance threshold (MAT) of 31,750. This MAT represents the number of wild fish that NOAA believes should return to reduce the long-term probability of extinction for the spring/summer Snake River Chinook Salmon population. In fact, all wild spring/summer Chinook escapement estimates above Lower Granite Dam since 2001 have failed to eclipse the MAT. These low returns of wild spring/summer Chinook Salmon are a concern for Fish and Game manager. Some actions we have been taking to try and improve wild Chinook Salmon returns include: implementation of habitat projects to increase spawning and rearing habitat, placing screens across irrigation diversions, hatchery supplementation, continued monitoring of key populations, and managing sport fisheries to minimize impacts to wild fish.

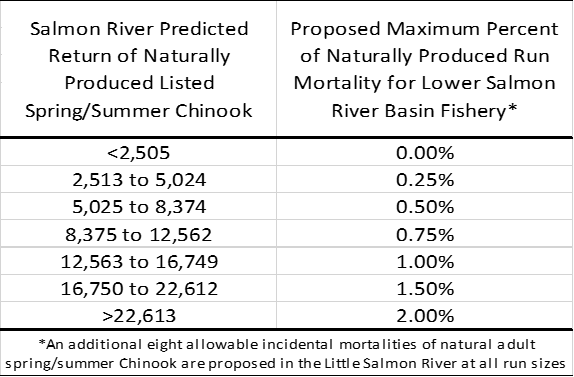

To ensure that sport fisheries are not responsible for reducing the long-term probability of persistence of wild spring and summer Chinook salmon, the IDFG manages its spring and summer Chinook Salmon fisheries so that impacts on wild fish do not exceed allowed take limits approved by NOAA. These take limits are defined in sliding scales that caps the number of wild incidental mortalities allowed dependent on the size of the wild return. For example, the table below shows the amount of impact that is allowed in sport fisheries in the Lower Salmon River based on the number of wild fish returning to the Salmon River basin. For example, if the return of wild Chinook Salmon to the Salmon River basin was 6,000 adult fish, a 0.5% incidental mortality rate would be allowed. This means no more than 30 (6,000 x 0.5%) wild incidental mortalities could occur before the fishery would be shutdown. To calculate the number of incidental mortalities that occur in a fishery, we assume 10% of all unclipped Chinook that are caught-and-released die. Additionally, any documented illegal harvest is also included in the total number of mortalities we estimate. There are different sliding scales IDFG follows anywhere fisheries occur where there are also ESA listed wild salmon. By following the guidelines in these tables, IDFG is confident that sport fisheries can occur without jeopardizing recovery of these important fish.