Here's your task: Clip millions of tiny fins off young salmon and steelhead so they can be identified as hatchery fish when they return from the ocean. Do it in a few months and at nine different hatcheries from Springfield to Orofino. You will also need to insert a needle-tip sized wire tag into noses of many of them, and a tiny electronic tracking device into hundreds of thousands of others.

That task used to take many people and lots of nimble fingers, but now it's been largely automated by a fleet of specialized trailers that do much of the work.

The process is vital to Idaho's salmon and steelhead fishing because it allows hatchery fish to be caught by anglers while also protecting wild and naturally produced fish. It also provides important data for fish managers, habitat-improvement programs, restoration and conservation efforts, hatchery origins, and more.

And then there's the "gee whiz" factor, which is hard to appreciate until you've seen the trailers and crews who operate them in action.

Juvenile fish are drawn from the hatchery's raceways into the trailer via pipes, tubes and pumps. Since the trailers are mobile, they can be moved reasonably close to the fish, but they still need access to high-volt power lines to operate the pumps, machines and computers that operate the machinery.

Fish come in at various sizes, and the clipping and marking machinery is calibrated to different sizes ranging from 2.2 inches to 5.6 inches. The fish are automatically sorted by size inside the trailer and fed into the appropriate machinery.

After being segregated by size into different trays, the fish are individually guided into the dark, rectangular boxes where their adipose fins are clipped and some also get a 1.1-millimeter long wire tag with an identifying number. Each trailer can mark about 100,000 fish per day. The trailers combined handle about 17 million fish annually.

That's the tiny fin that must be removed. It's smaller than a match head. The missing adipose fin is how anglers typically know they can keep a salmon or steelhead they catch. If biologists are trying to rebuild runs in areas that have become depleted, they might release some unclipped fish so they can escape anglers, or in rare cases, so they can escape downstream anglers to provide fishing opportunity farther upstream.

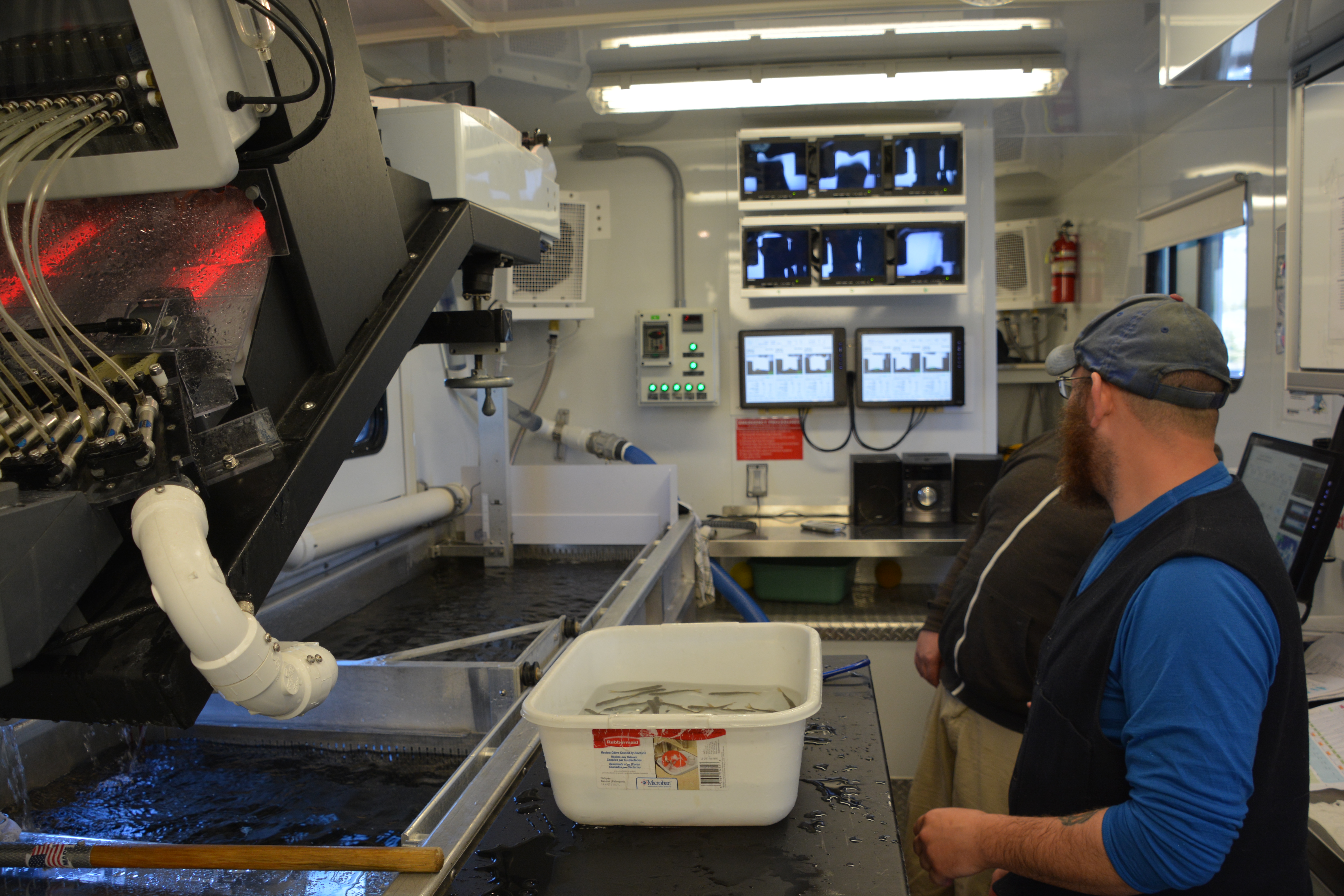

Fish marking trailers are combination computers, video cameras, machinery and human operators. There's a lot of moving parts, and equipment that needs constant attention because they're dealing with small, fragile fish. The survival rate is well above 99 percent because after being sorted, the fish are clipped in a matter of seconds, never leave the water, and most are never touched by human hands. They're back in their raceways minutes after entering the trailer. But operators have to keep a close eye on the whole process. "You've got to have your head on a swivel and be aware of the situation at all times," supervisory fisheries biologist Michael Friedrich said.

While the machines are reliable, some fish still get clipped the old fashioned way, particularly when a fish is too big for the machinery or it rejects it for some other reason. Fisheries technician Chris Heffner of Lewiston and others there to clip the fins manually and also keep an eye on the operation.

Crews also manually inject "PIT" tags into about 250,000 to 300,000 fish annually, which are small electronic tracking devices about the size of a grain of rice. Unlike wire tags, PIT tags transmit a signal so biologists can track outmigrating smolts, then also recognize them as returning adults when they cross dams. That information lets biologists know approximately how many fish survive the trip to the ocean, and about how many return, so they know not only how many fish are coming to Idaho before they get here, but which hatcheries or release sites they are heading toward.

Marking trailer crews typically work in two shifts from 6 a.m. to 11 p.m. during marking season, which runs from spring until fall. Each trailer costs about $1.1 million, and they are a cooperative between Idaho Fish and Game, U.S Fish and Wildlife Service, Pacific States Marine Fisheries Commission, Lower Snake River Compensation Plan, and Idaho Power Company.