Reprinted by permission from Idaho Game Warden Magazine.

WOW! It’s been around 17 years since the crash of the yellow perch fishery in Lake Cascade. We’ve come a long way since then. Idaho Department of Fish and Game fishery biologists went down many paths figuring out why this fishery had crashed and how to recover it. We then had to implement a recovery plan and hopefully have it work. I’ve spent my entire career of 24 years with the Idaho Department of Fish and Game in McCall and much of that time has been spent working on Lake Cascade with perch. So I’ve had the privilege of working and living this entire project from beginning to where we are today.

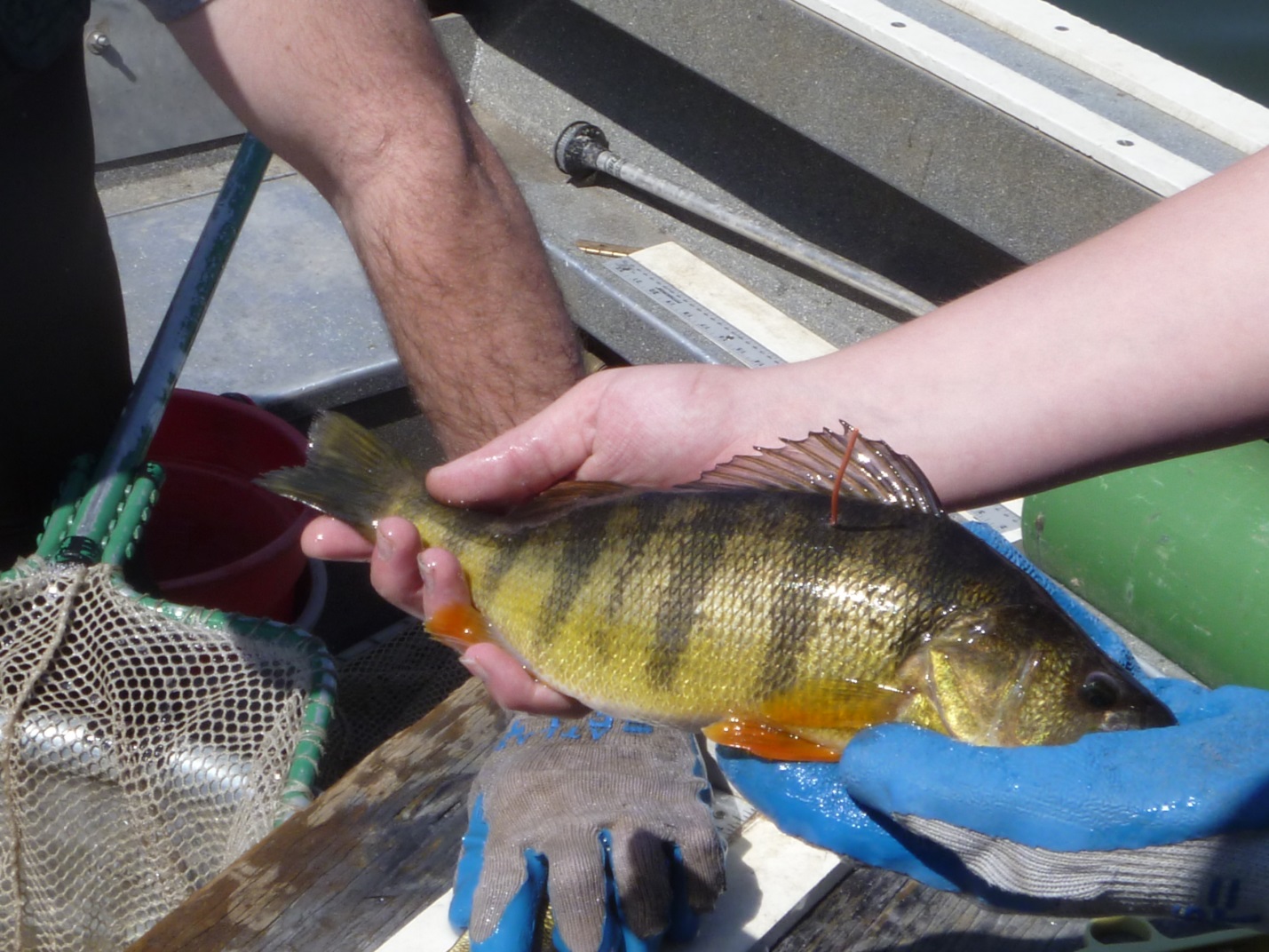

We now have state record perch and plenty of rainbow trout swimming around the lake providing for some great fishing. Gone are the days when we’d count less than 20 fishing boats on a Memorial Day on this 28,000 acre lake.

From the early 1980’s through the 1990’s, large catches of large perch were common and even expected. To illustrate how valuable the perch fishery was prior to and after the collapse here are a few facts. In the 1980’s Lake Cascade was the #1 fishery in the state and in 1992 it was estimated to be worth over $16.5 million to the local and state economy (2011 dollars). In 2009, three years after the recovery began the fishery was valued at only $3.4 million (2011 dollars). I would guess that in 2001 this number was much lower as the perch fishery was virtually non-existent.

After all these years I was asked to give a Readers Digest version of this project; why the perch fishery crashed, how the Idaho Department of Fish and Game figured out what went wrong, and how we recovered the fishery.

This Journey began in 1997 when anglers contacted the McCall IDFG fishery biologists with stories of poor perch fishing in Lake Cascade (Cascade Reservoir at that time). We were somewhat skeptical at the time as previous fish surveys indicated good numbers of all sizes of yellow perch in the lake. With all the poor fishing reports we put together a sampling strategy and out we went to investigate.

We were totally surprised by the results. There had been no survival of juvenile perch since at least 1989. We found virtually no perch greater than 4 inches in the lake. Now we were really concerned. What the heck had happened to all the adult perch?

We quickly put together a study plan to figure out what was happening. We looked especially close at water quality. In the 1990’s Cascade Reservoir looked much different than it does today. There were serious water quality issues as a result of too many nutrients entering the lake. McCall City sewage effluent, cattle, logging, roads and erosion all contributed to the problem.

There were huge blue-green algae blooms in the lake by late summer. The water was pea green with floating mats of algae so thick you couldn’t get a boat through them. The spray off a boat traveling at high speed looked like pea soup. There were cattle and dogs killed by drinking lake water contaminated with blue-green algae toxins. The lake was a mess. Blue green algae blooms of this magnitude can use up oxygen in a lake in a short time, especially in confined bays and under ice conditions which will kill fish.

In the 1900’s and early 2000’s we observed relatively small fish kills in isolated areas around the lake and after ice out. Probably due to low oxygen conditions. However we did not show that this was a serious problem lake wide.

Concurrently with IDFG’s work on the perch fishery the Idaho Division of Environmental Quality initiated a Lake Cascade water-quality improvement plan. This plan was a huge success and by the late 2000’s water-quality in Lake Cascade had improved dramatically. We no longer see the huge blue green algae blooms that had plagued the lake for so many years.

We looked at how many perch went through the dam during high flow releases and we looked at perch food abundance in the lake. Neither of these showed significant impacts to perch and their decline.

We observed some sick juvenile perch collected in our fish sampling gear, probably related to poor water quality. We also collected many juvenile perch infected with a small parasite. However, this parasite was not known to cause mass die offs of perch in other parts of the country. Our studies showed that disease and water quality issues probably contributed somewhat to the crash in perch numbers but was not the main culprit. These issues would not have targeted only fish larger than 4 to 6 inches.

Annual sampling of the perch population showed no improvement and we were still at a loss as to a cause. Why were virtually no perch living past the age of two?

The last thing to examine was predation on young perch by the only large predator in the lake, the Northern Pikeminnow (Squawfish). In 2000 we examined the impacts of Northern Pikeminnow predation on perch. We placed four net pens around the lake and stocked them with a known number of 1 year old perch.

The net pens were large enough to allow the small perch to forage for natural food which drifted into the nets. However the nets protected the small perch from predators.

Also perch in the pens were still vulnerable to disease and low oxygen levels. If penned fish died we could infer that predation was not the primary cause of perch mortalities. However, if perch lived and flourished in the pens while perch in the lake continued to die we would have our answer to the cause of the decline, PREDATION.

After six months the perch in the net pens were alive and well and had grown a couple inches. We finally had our answer! Northern Pikeminnow were literally eating up all the yellow perch in the lake and had destroyed the perch fishery.

Subsequent studies showed there could be as many as 500,000 Northern Pikeminnow in the lake in the 1990’s. University of Idaho food studies indicated that 500,000 Northern Pikeminnow with a diet of 10% perch would consume 68 million perch in one year.

So now what do we do? This is no small lake at 28,000 acres. We can’t use a fish toxicant to kill all the fish in the lake and start over as we would in a small lake. It would take millions of dollars and would be logistically impossible. Also, there isn’t enough chemical in the world to do this big of a treatment.

In 2001 we began trapping Northern Pikeminnow as they migrated up the North Fork Payette River in the spring to spawn. This was a tough task as fish migrated up the river just after the peak of snow runoff. High river flows made trapping nearly impossible in the best years and totally impossible in high flow years.

We kicked around more ideas and thought if we couldn’t treat the water to get rid of Northern Pikeminnow maybe we could get rid of the water. Our first proposal was to drain the lake as low as possible and then chemically treat the small lake that remained and then refill the lake the following year. Then restock with perch and trout. Sounds fairly simple but was far from it when you think about all the users of water that comes out of Lake Cascade (primarily irrigators, salmon flow augmentation, and Idaho Power Company).

In 2003 we went to the U. S. Bureau of Reclamation with our plan and spent thousands of dollars modeling different water year scenarios to determine if the plan was feasible in terms of assuring that all water users would get the water they needed the year after draining. We mailed out flyers to every resident in Valley County describing our plan. Some of you I’m sure remember it. The Department was also prepared to spend hundreds of thousands of dollars for a full blown Environmental Impact Statement for the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation.

In 2004, after a lot of money and time was spent, the proposal was withdrawn due to the potential shortage of water to meet downstream water obligations the year following the draining.

Immediately following the decision we moved on to plan B: To kill as many Northern Pikeminnow as possible and to stock as many adult yellow perch as we could over the next three years. This was a huge undertaking logistically and monetarily.

The Department purchased an electric fish barrier for $40,000. This stopped the Northern Pikeminnow spawning migration up the North Fork Payette River at Hartsal Bridge. When several thousand fish were backed up below the barrier we then used a fish toxicant to remove them. We repeated this every three or four days until the migration was over each year.

We killed thousands of Northern Pikeminnow. This was repeated three years in a row from 2004 to 2006. In 2006 virtually no fish were observed migrating up the river as we had effectively killed most of the fish that spawned in the North Fork Payette River. We also purchased six large 10’ X 20’ fish traps that sat in lake and were effective at capturing Northern Pikeminnow for removal.

Department studies suggested we would need to transplant anywhere from 60,000 to 1.2 million adult perch in Lake Cascade to make it work. This depended on numbers of Northern Pikeminnow still remaining in the lake and the size of perch that were transplanted.

We searched high and low for lakes with high perch numbers, disease free, and as close to Lake Cascade as possible and found two; Phillips Reservoir, Oregon and Lost Valley Reservoir, Idaho. Immediately after ice out in 2004 through 2006, the large trap nets were placed in these lakes and collected as many adult perch as possible during their spawning activity. Captured perch were transported on large fish transport trucks and released into Lake Cascade. We also transplanted a small number of perch from Lake Mary Ronan in Montana, and Montpellier and Horsethief Reservoirs in Idaho.

We collected and transported 865,000 adult perch over the three years. It took over 60 truckloads to haul perch to Cascade. The trips to Phillips Reservoir took about 10 hours to complete. Overall it was a huge undertaking and a huge success. Again, over the same time period we had removed thousands of Northern Pikeminnow!

Signs of a perch recovery came quickly. Over the last nine years the transplanted perch have spawned and their progeny have spawned, pumping out millions of juvenile perch. Because the lake was virtually void of perch when the new perch were transplanted they had an unlimited food supply. This resulted in amazing growth rates for perch.

Over the last four years we’ve had two state record perch caught and one fish tying the record. Word has spread around the country of the world class perch fishing. It’s been written about in fishing magazines and had outdoor television shows feature Lake Cascade (from Minnesota no less!).

In 2011, the fishery was well on its way to recovery and the estimated economic value was $11.5 million.

Here we are in 2015 and the Lake Cascade perch population is doing well. However, the perch population is still in the process of sorting out where it will end up in terms of total population size, growth rates, and what the maximum size of fish will be. We continue to monitor perch and northern pikeminnow numbers to avoid future problems.

To complete the perch studies and recovery efforts the Idaho Department of Fish and Game invested over $1,000 000 of Idaho fishing license dollars. A sound investment when compared to the value of this fishery to local and state economies of Idaho.