The Panhandle region placed 172 GPS radio-collars on 6-month old elk calves in the Coeur d’Alene and St. Joe River drainages since 2015. A couple reasons we collared so many elk was to determine survival rates and for those elk that didn’t make it, find out why they died.

The GPS collars have a signal that activates once the collar hasn’t moved for several hours, indicating a mortality. Next, the collar sends an e-mail to biologists with the location of the collar. It’s pretty amazing technology, something that wasn’t available just a few years ago, and it’s giving us new insight into what’s affecting the elk population. We try to hike out to every dead elk within a day or two of receiving the mortality signal so we have the best chance of figuring out what happened.

It can be difficult to look at a partially consumed elk carcass and determine how the animal died. The more of the elk that is there, the easier it is to figure out what happened. We want to find out why it died, or in our language, determine cause-specific mortality. That’s why we try to get to the elk as soon as possible.

Once we get to the location and find the elk, we take a crime scene approach. We conduct a careful search around the carcass looking for predator tracks, hair, drag trails in the dirt or snow, broken branches that indicate a chase, and blood on vegetation or the ground. Next, we perform a necropsy (basically an autopsy for an animal). We skin the entire animal looking for teeth or claw punctures and bruising on the skin or muscles (which means that something injured it while it was still alive). We look for broken bones, parasites, and abnormalities of the internal organs. Lastly, we saw open a femur bone to examine bone marrow. Bone marrow is normally hard and white and is the last fat reserve the body uses during starvation. Soft and red bone marrow means the elk was in very poor condition when it died.

The two most common predators that kill older calves in the Panhandle are mountain lions and wolves, but their kill patterns are quite distinctive, hence the crime scene approach. Lions tend to ambush and bite the neck or throat of their prey. The attack site and the kill site are often close together. Lions often drag their prey to a more hidden spot and will cache the animal by covering it with snow, leaves, or needles. Lions have a habit of shearing hair, which looks like someone cut the hair with sharp scissors. Lions often enter the chest cavity first and eat the internal organs.

Wolves, on the other hand, are not ambush hunters. They typically chase their prey long distances, biting hindquarters, flanks, neck, and face. Wolves will eat the animal where it died and often scatter the carcass throughout the site as each wolf takes its own piece to consume. Wolves will often chew on all the bones. The site of an animal killed by wolves is often a much messier scene than that of one killed by a mountain lion. There’s often very little of the carcass remaining when we get there.

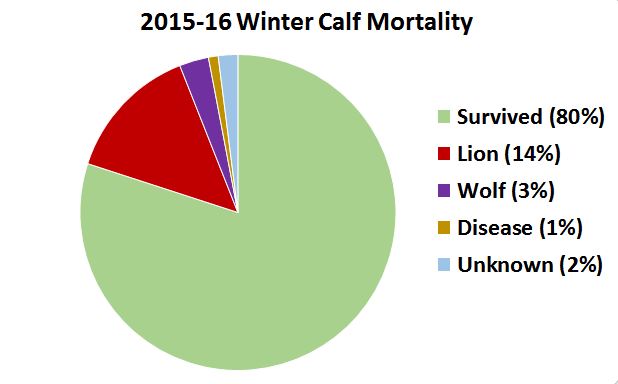

So, what have we learned? In the normal to mild winters of 2015 and 2016, 80% of the elk calves survived from January to June; 14% were killed by mountain lions, 3% were killed by wolves, 1% died of disease, and 2% were unknown deaths. A survival rate of 80% for 6 month old calves is very high.

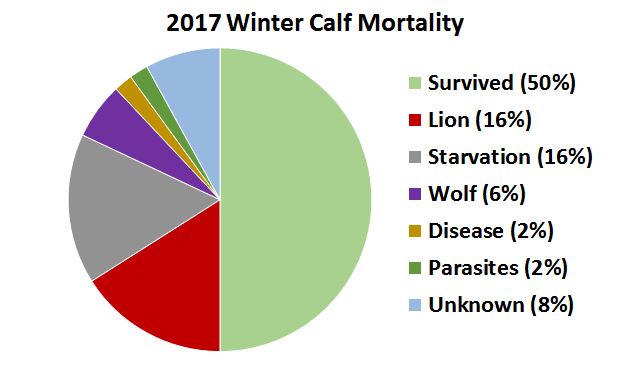

In the colder, snowy winter of 2017, 50% of the elk calves survived. Interestingly enough, the predation rates were similar to the milder winters; 16% were killed by mountain lions and 6% were killed by wolves. Starvation (16%), heavy parasite loads (2%), and disease (2%) accounted for the difference in survival rates among the winters. Calves were in worse body condition in 2017 as determined by bone marrow condition. We could not determine cause of death in 8% of the cases.

What do these calf survival rates mean for the elk population? We are working on some modeling now, incorporating other information like cow survival rates, calf:cow ratios that we get during our winter aerial surveys, and the percent of spikes in the harvest. Once we get the results of the modeling , we’ll report to you on that.

Our jobs can certainly be gruesome at times, but it rewarding to determine what is happening with our elk populations so we can make informed management decisions.