After sending a recent e-mail about our poor steelhead A-run, one of the most common questions I got was, why would this run be so poor? I probably dug into this more than I should have, which may bore some with all my graphs, but I wanted to make sure I answered all the questions people asked.

It’s important to keep in mind that as you read through this that I am referring to the poor steelhead A-run. Most of these fish migrated to the ocean in the spring of 2016 and spent just one year in the ocean before returning this year (2017). We are still waiting to see how the B-run materializes over the next month or so.

There are many things that can influence the survival of steelhead, and they can vary depending on if you are considering wild fish or hatchery fish. For example, wild fish typically rear two to three years in fresh water before migrating to the ocean. As such, stream flow, summer and winter water temperatures, habitat conditions, and the number of adults that spawned can all influence survival and the number of smolts that eventually migrate to the ocean.

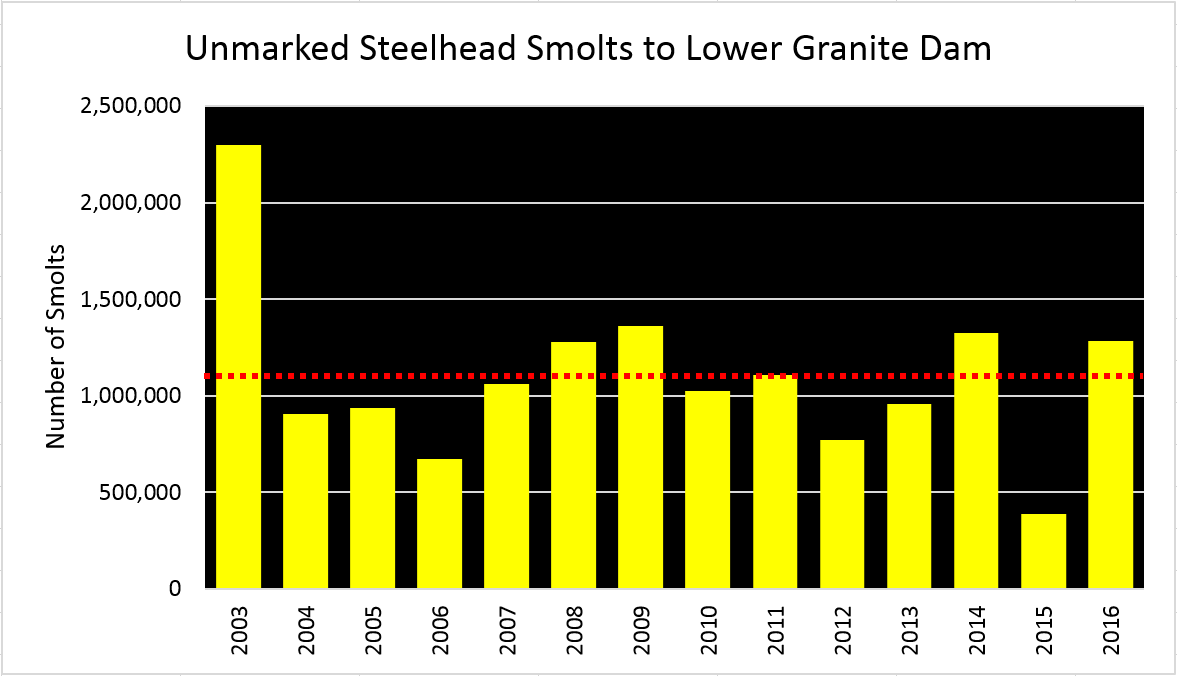

The hot, dry year in 2015 certainly reduced survival, and the number of wild steelhead smolts that out-migrated from some watersheds in 2016 (Knoth et al. In Prep). However, if you look at the figure below, the estimated number of wild steelhead smolts that passed Lower Granite Dam in 2016 were actually higher than average (dotted red line) when compared to the last 13 years (Fish Passage Center data).

Idaho hatchery fish, on the other hand, are reared for one year in a fairly consistent environment. Therefore, if there are no major disease outbreaks, or changes in hatchery practices, the number, size, and condition of the smolts released do not vary much from year to year. Based on my communication with Idaho’s hatchery facilities, there were no major disease outbreaks or changes in hatchery practices that could explain for the low returns this year. In fact, hatchery release goals were met or nearly met at all our hatcheries in 2016.

Once hatchery and wild steelhead begin their migration to the ocean as smolts, they face similar conditions that will influence their survival to adulthood. Downstream migration conditions and ocean conditions are the two biggies that I am going to discuss in more detail.

I know many people have expressed concerns to me about predators (fish, birds and seals/sea lions); but because I’m not aware of large changes in predator abundance (or factors that would make them more efficient) that could explain for this huge downturn in steelhead returns, I am not going to discuss it here. Yes, pinniped numbers are increasing in the Columbia River mouth and they are eating more salmon and steelhead; but seals and sea lions leave the Columbia River in June and July before summer steelhead (Idaho’s steelhead) arrive (Wargo Rub et al. 2016).

Research has shown that flow can influence survival of steelhead smolts as they migrate downstream. The general trend is that low flows are not good for smolt survival. What makes the relationship between river flow and smolt survival difficult to assess is that over time changes have occurred in other areas known to influence survival like the amount and type of spill that occurs at dams, the number of fish transported in barges, and the number of predators.

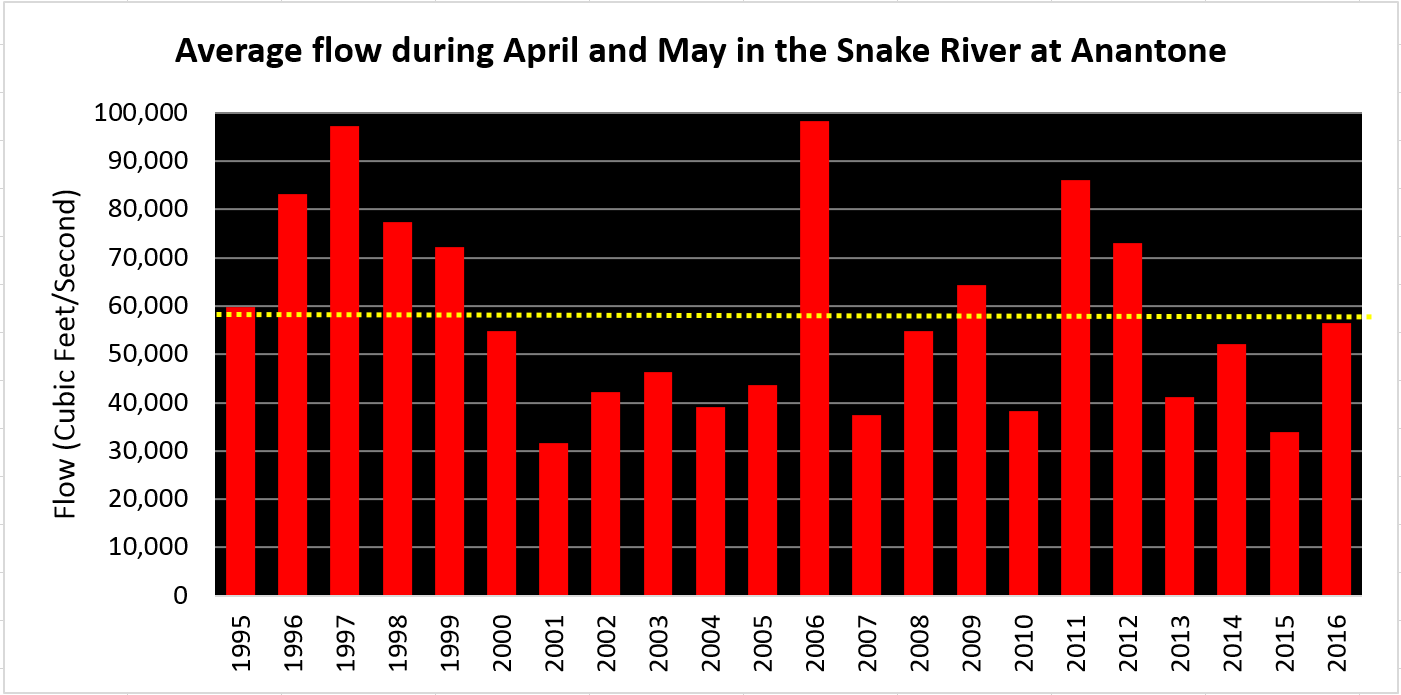

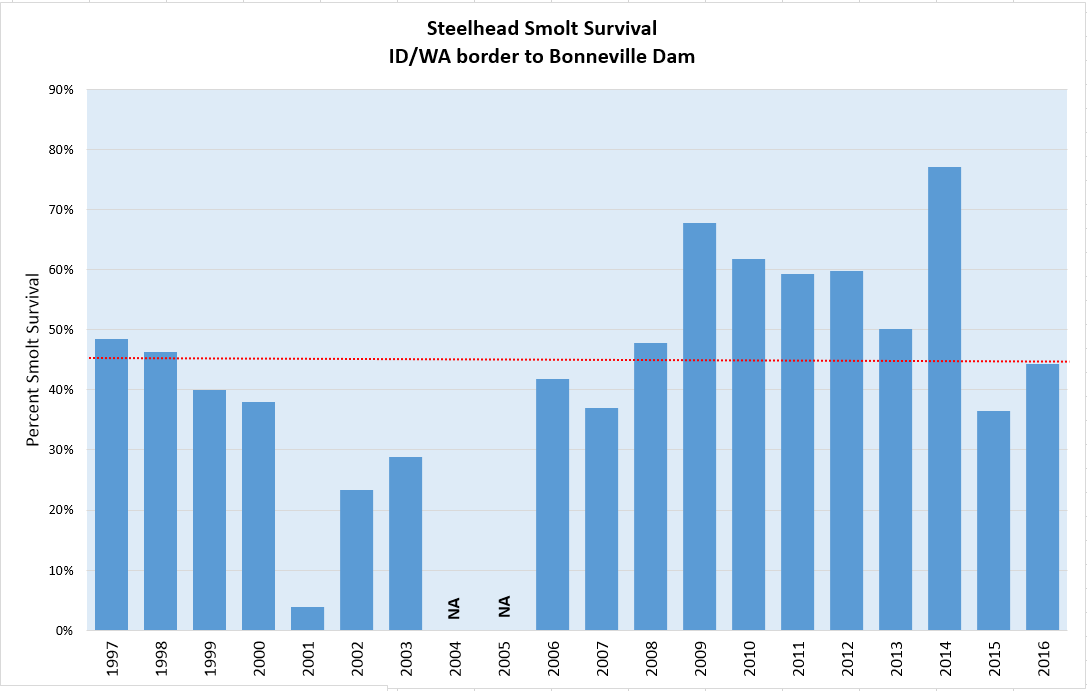

I’m not going to get into the details for these different issues, but I do want to show you how flow has changed in the Snake River over time. The figure below shows the average flow during April and May in the Snake River at Anatone (just upstream of the Idaho/Washington border) when peak steelhead migration occurs in this area. As you can see from this graph, flows in 2016 were about average (dotted yellow line) suggesting low flows were not responsible for this year’s low A-run return. In fact, if you look at steelhead smolt survival (see figure below in blue) from the Idaho/Washington border downstream to Bonneville Dam, survival appeared about average when compared to the past 20 years (Faulkner et al. 2017).

If the number of out migrating smolts was not abnormally low in 2016 (compared to the last 20 years) and flows and survival were about average (for the last 20 years), that leaves ocean conditions as the main driver for this year’s abnormally low return.

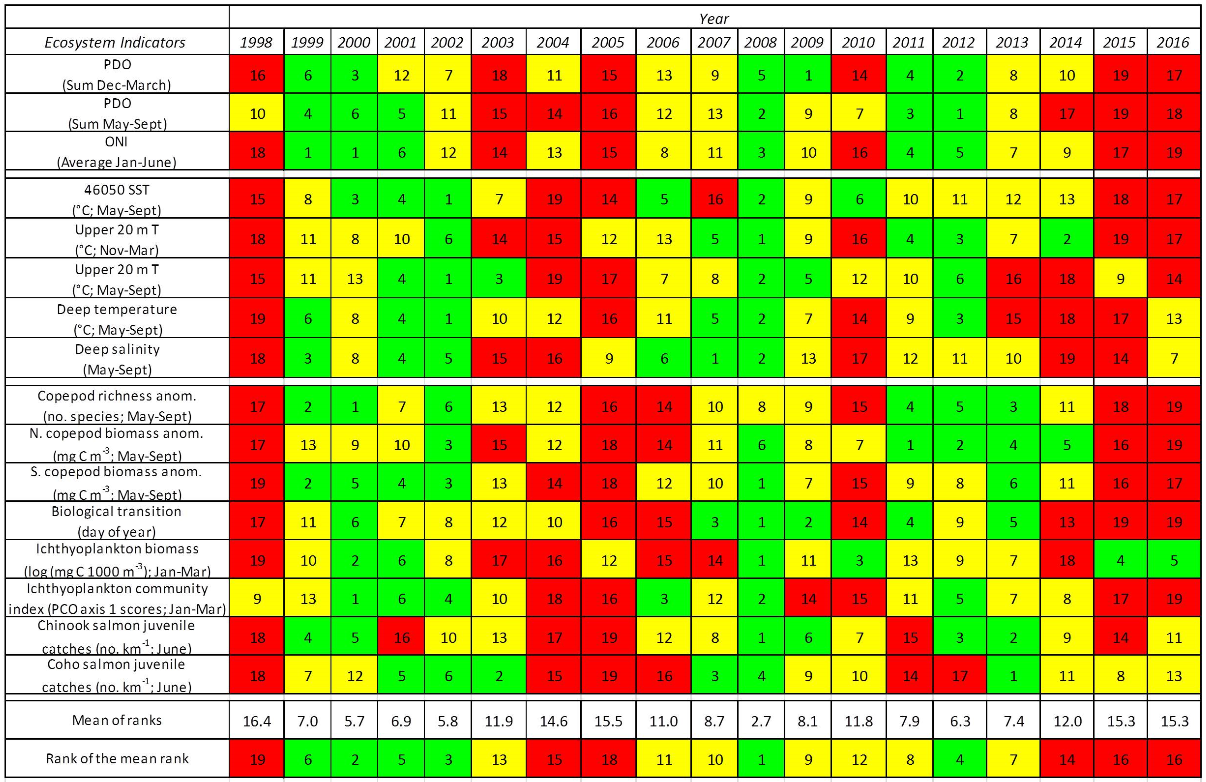

There are many things in the ocean that can influence survival of salmon and steelhead. In fact, if you look at the checkered table below, it lists a multitude of factors that have been correlated with survival of salmon and steelhead in the ocean. This table actually shows how these particular factors ranked (low number/green being good and high number/red being bad) over time in relation to salmon survival in the ocean.

One could speculate that these conditions would also apply to steelhead survival as salmon and steelhead have many similar behaviors. If you focus on the last row of this table, it averages out all these rankings to give an overall rank for each year. The year of 2016 ranked 16 out of 19 meaning ocean conditions were not good for salmon and steelhead. If you are interested, this data and many of the proceeding figures came from this website. https://www.nwfsc.noaa.gov/research/divisions/fe/estuarine/oeip/figures/Table_SF-02.JPG

This data suggested we would have a poor steelhead return this year, but it didn’t suggest that we would have one of the worst runs we have seen in the last 50 years. Now, I certainly am not an ocean expert; but when I look at this data, there is one area that catches my eye. That is the section that pertains to the type and amount of food that was available (the rows referring to copepods and ichthyoplankton).

Many of these rows have the worst ranking (19) we have seen since this data has been collected. This suggests that the amount of preferred food available to young steelhead entering the ocean and smaller fish that larger steelhead eat was extremely bad. One of the more important food sources for young steelhead and smaller fish are copepods, but not all copepods are created equal.

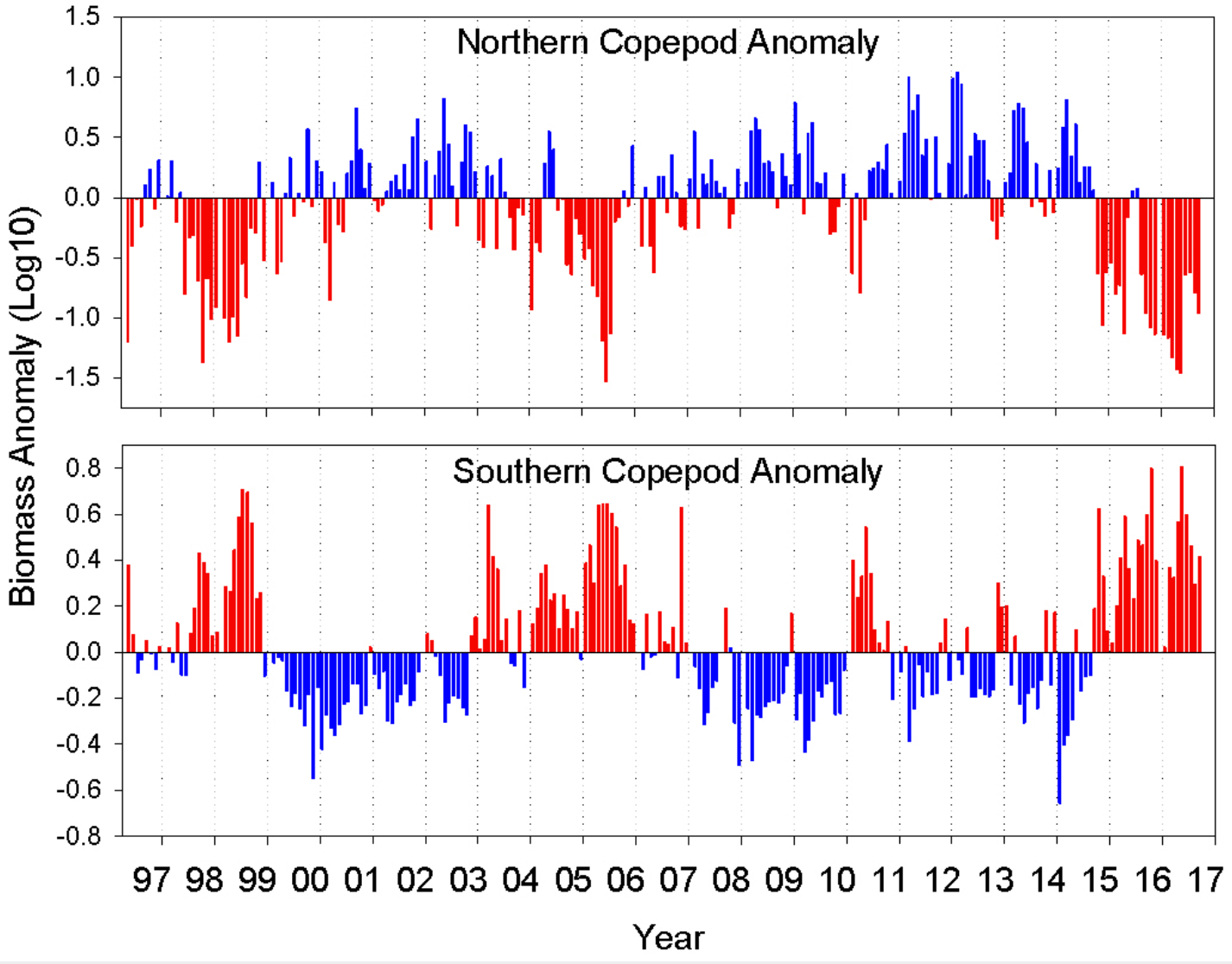

Northern strains of copepods typically dominate the Washington/Oregon coastal zooplankton community during the summer. These northern copepods tend to be larger and fat-rich providing smaller fish important calories needed to grow and survive through winter. Southern strains of copepods are smaller and have less fat in them essentially providing fish a “low calorie” diet. Data shows that when northern copepods are abundant, survival of salmon and steelhead goes up, whereas when southern copepods are abundant, survival goes down.

The figure below shows how the biomass of northern and southern copepods have fluctuated in comparison to average since 1997. What is very apparent is that in all of 2016, northern copepod biomass was down and southern copepods abundance was up. This doesn’t bode well for salmon and steelhead survival.

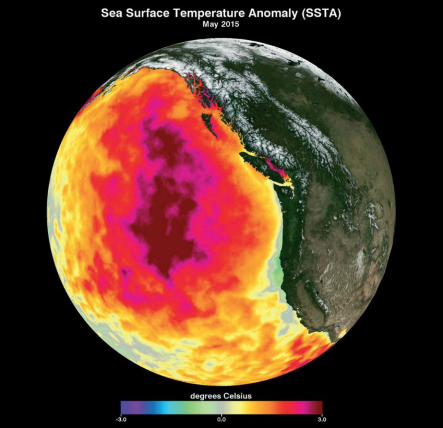

Finally I should mention “The Blob”. This was the term given to the massive area of unusually warm water located off the coast of the Pacific Northwest.

This condition peaked in 2015, but persisted into 2016. These water temperatures were so unusual that we really did not know what level of impact it would have on salmon and steelhead survival. Associated with “The Blob” was poor nutrient levels, low biomasses of zooplankton, and warm water species typically not present in northern latitudes. These are all factors not favorable to steelhead survival.

As you read this, it is obvious that I am pointing at poor ocean conditions for the reason this year’s steelhead A-run is extremely low. However, I need to emphasize that continued improvements to spawning and rearing habitat and the migratory corridor can make a difference in salmon and steelhead returns. In fact, I would argue that in years like this, if we had better spawning, rearing, and migratory conditions, it could buffer the poor ocean conditions to the point that we could still provide harvest fisheries in Idaho, and wild fish would not be threatened of going extinct. - Joe DuPont, Clearwater Region Fisheries Biologist