by Tiege Ulschmid and Joe DuPont

Every year hundreds of wild adult steelhead make the 500 mile journey from the Pacific Ocean to the Potlatch River, a tributary to the Clearwater River about 15 miles upstream of Lewiston, Idaho. It is here they will spawn to create the next generation.

Unfortunately, the steelhead population in the Potlatch River is only a fraction of what it once was. Locals tell stories of when their families once caught numerous steelhead in streams that are now dry. Years of habitat degradation from farming, logging, grazing and human development has taken its toll on this river. Idaho Department of Fish and Game biologists have spent the last 11 years studying this steelhead population, and we now better understand where these fish spawn and rear and what can be done to increase their survival. For these reasons, it was decided to embark on a major habitat restoration program in this basin to increase the number of steelhead that will ultimately call the Potlatch River “home”.

It is going to take a lot of work, time, and money to rebuild this steelhead population back to what it once was. Fortunately, there are many partners teaming up to make a difference such as the Idaho Department of Fish and Game, Latah Soil and Water Conservation District, Bonneville Power Administration, Office of Species Conservation, Idaho Department of Lands, U.S. Forest Service, Natural Resource Conservation Service, Potlatch Corporation, and Bennett Lumber. But most importantly we depend on private landowners. The large majority of the Potlatch watershed is privately owned; and without willing landowners, this program would not succeed. Fortunately, there are landowners who want to see steelhead flourish once again in the Potlatch River and are joining in to make a difference.

Based on our research, we believe we can make a big difference in rebuilding steelhead in this watershed by concentrating our restoration efforts in the following three areas:

- Increasing summer flows in stream reaches that go dry or have very little water

- Removing barriers (such as old or outdated culverts) that cut off access to historical spawning and rearing habitat.

- Restoring in-stream habitat to provide cover and rearing habitat for juvenile steelhead.

To accomplish these goals, we often use very different strategies. Although we are relatively new to this restoration program, we are learning and seeing some encouraging things we’d like to share with you.

Increasing Summer Flows

One thing is for certain, steelhead need water to survive. Unfortunately, many historic practices focused on removing water from the land as quickly as possible so that it could be more easily farmed, grazed, and/or developed. These practices have resulted in many stream reaches that once supported steelhead to now go dry or mostly dry during the summer. Restoration activities that will increase summer low flows in these streams can make a big difference on how many steelhead they can produce.

One example of work we are planning that can immediately increase summer low flows is to release water from an upstream reservoir. The Department of Fish and Game owns a reservoir in the headwaters of Spring Valley Creek; and by releasing water from this reservoir during critical periods, it can maintain summer flows in a 10 mile reach of stream that would otherwise mostly go dry. We suspect this will immediately increase steelhead survival and could increase steelhead production by thousands of juvenile fish in this watershed. This strategy will require modifications to the reservoir to protect its own intrinsic value, but the fix will be very economical compared to the cost of traditional restoring strategies used to increase summer flows.

Throughout most of the Potlatch watershed we don’t have this unique opportunity to increase summer low flows. As such, we will rely on strategies such as reconnecting floodplains, restoring native vegetation, and putting sinuosity back into streams. The goal of these types of projects is to create a system where the surrounding land can absorb water during spring runoff, similar to a sponge, and then slowly release it through the summer creating a year round flowing stream. With these types of projects, we must have patience as it can takes years before a system can repair itself back to historical type conditions.

Barrier Removal

The nice thing about removing barriers is we have learned that steelhead will quickly explore and re-occupy lost habitats. For example, the Troy dam, outside of the city of Troy, Idaho, was built in the 1930’s as a means to provide water to the city. Even though the reservoir completely filled with sediment in three years, it took 70 years before the dam was finally removed. The very next year after the dam was removed, steelhead were documented moving past the dam site and spawning in areas that had been blocked off for years.

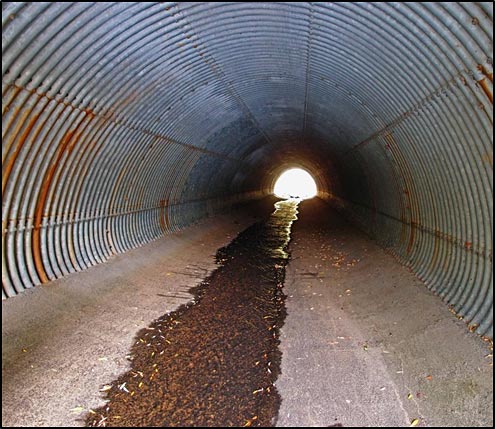

We have identified other barriers in the Potlatch watershed that if removed will immediately provide new habitat for steelhead to occupy. For example, there is a highway culvert on Big Meadow Creek that blocks access to 10 miles of stream and another on Spring Valley Creek that limits access to another 10 miles. Big Bear Creek has a waterfall barrier that, due to upper watershed manipulations over the last century, has turned the creek into a firehose during the spring steelhead migration severely limiting passage past these falls. The IDFG is currently working with funding agencies to identify where barriers occur and restore access to this lost habitat.

As these barriers are removed in the Potlatch, steelhead will once again occupy areas in the watershed that have been inaccessible for decades. This will increase the overall area for more fish and allow them to spread out and reduce competition for space and food.

Restoring In-stream Habitat

In the upper Potlatch River basin, historic timber practices and development have had an influence on stream habitat. Roads and railroad grades were often constructed up stream bottoms to access the timber; trees along the streams were heavily harvested as they were often the easiest to get to; and stream channels were straightened and cleared to reduce flooding of roads, pastures and buildings. These activities led to straighter stream channels and removed the very things that steelhead need to survive – shade, hiding cover, velocity breaks, different substrate sizes, and food sources. Work by IDFG shows that many juvenile steelhead migrate out of the upper Potlatch watershed a year earlier than normal, assumedly to find better habitat downstream. For this reason, IDFG has focused restoration activities in the upper basin that will improve in-stream habitat.

Our strategy is to focus our in-stream restoration efforts on the East Fork Potlatch River watershed since we determined steelhead production in this basin is limited by a lack of channel complexity. Restoration actions that have occurred included adding large woody material, placing streams back into their historic channel, fencing out live stock, and planting riparian vegetation. Monitoring efforts are showing that we are on the right track with these improvements as we are seeing increased densities of steelhead where these restoration activities are occurring.

As a final note, we want to emphasize once again that none of this is work is possible without cooperation from landowners. The most important link is the landowner who is willing to listen to these philosophies and science and take the step to let us work with them to restore the habitat.